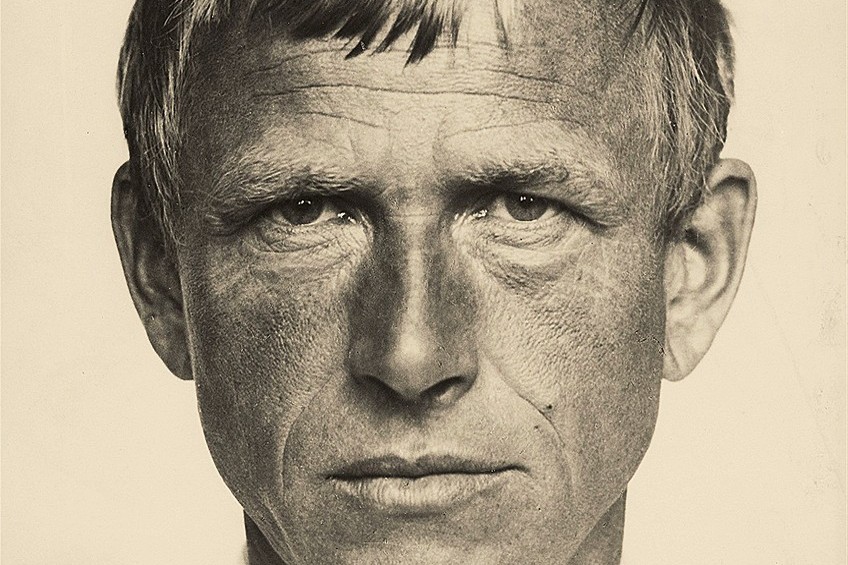

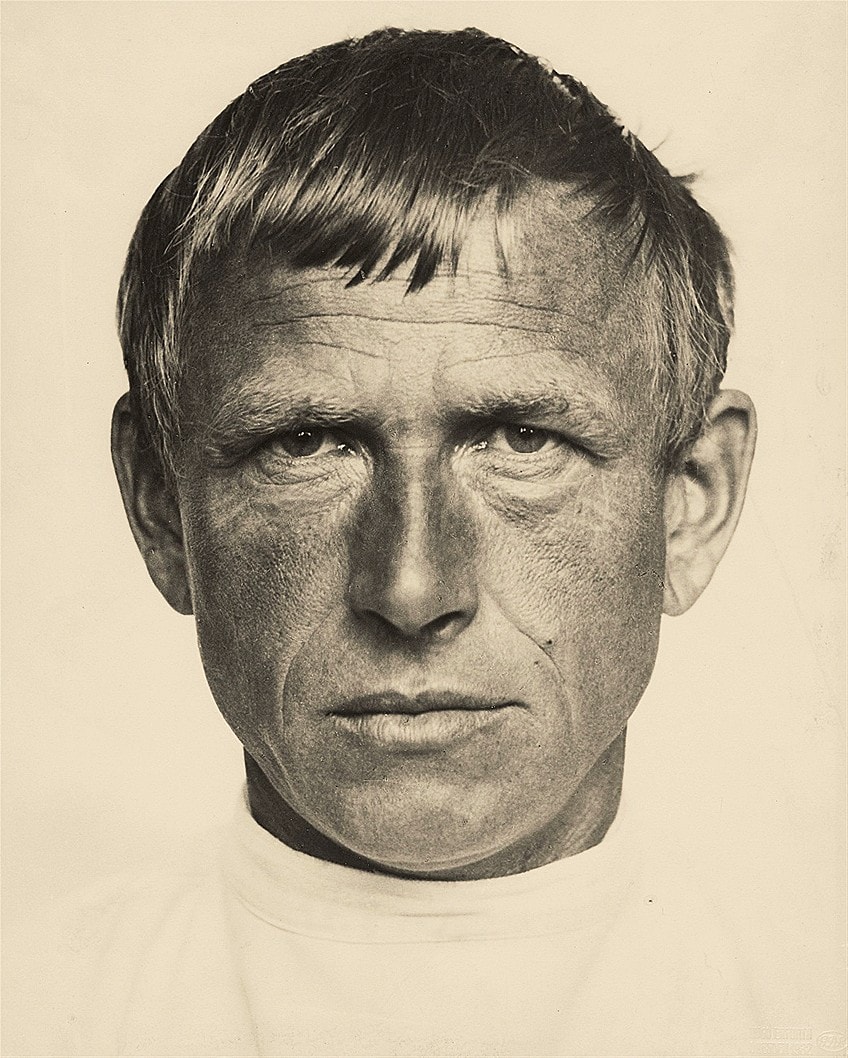

Otto Dix – Scathing Satirist of German Brutalities

Otto Dix may have had more influence than just about any other German artist in molding public perceptions of the German Empire in the 1920s. Otto Dix’s paintings are important components of the “New Objectivity” school, which also captivated Max Beckmann and George Grosz in the mid-1920s. His first big subjects, as a war vet traumatized by his ordeals in WWI, were maimed soldiers such as in Otto Dix’s The War (1932) painting, but towards the prime of his career, he also portrayed nudes, brothels, and often ruthlessly sarcastic pictures of intellectuals from Germany.

Table of Contents

A Biography of Otto Dix

| Nationality | German |

| Date of Birth | 2 December 1891 |

| Date of Death | 25 July 1969 |

| Place of Birth | Untermhaus, Germany |

In the early 1930s, Otto Dix’s paintings grew even gloomier and more metaphorical, and he became a Nazi target. As a result, he progressively turned away from societal issues, focusing on landscapes and Christian themes, and eventually earned tremendous success after serving in the military during WWII.

Otto Dix is remembered as one of the most vicious satirists in modern art.

In the 1910s, when many painters had eschewed portraiture in favor of abstraction, Dix reverted to the field and incorporated biting caricatures into his representations of some of Germany’s major figures. His other story topics are famous for their condemnation of modern city corruption and immorality.

Childhood

On the 2nd of December, 1891, Wilhelm Otto Dix was born to Pauline and Franz Dix. Dix acquired strength of character from his father, who worked as a mold caster in an iron foundry. His mother instilled in him a passion for poetry and music. During primary school, he initially demonstrated his artistic abilities, particularly in sketching.

He began modeling for painter Fritz Amann when he was eleven years old and was so inspired by his time in the studio that he chose to pursue a career as a painter.

Ernst Schunke, his high school art instructor, led him through his studies and assisted him in obtaining financial aid. He had to acquire a skill while continuing to study art under Schunke as part of the prize, so he worked as an assistant designer for four years.

Early Training

Dix enrolled in the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts in 1909. With a globally acclaimed music and art community that held massive exhibits and concerts, the city produced a vast amount of creative output. Dix did not have to worry about money throughout his time at art school; after the first semester, he was free from owing fees and was given an allowance. He supplemented his income by painting miniature portraits and genre artworks and coloring pictures.

The Academy did not provide an academic artistic education, but rather a more craft-oriented one. Dix was primarily a self-taught artist as a consequence.

But, with the help of Richard Guhr, he tried his hand at sculpture. He produced a sculpture of Friedrich Nietzsche for the Dresden State Museum, but it was subsequently demolished by the Nazis. Dix learned how to work in the style of the Old Italian, Dutch, and German master painters by studying their ways of layering paint to produce dimension and brightness.

The Expressionists and Post-Impressionists, especially a Vincent van Gogh exhibit he visited in 1913, left a lasting impression on him. Dix dabbled with pen and ink and created his first prints in 1913, primarily producing landscapes and portraits.

Mature Period

When WWI broke out, Dix gladly enlisted for duty and was recruited into a field artillery unit; but, by 1915, he was a machine gunman on the forefront in France, and his experiences in numerous horrifying battles had soured his zeal. Despite being injured multiple times, he was able to reproduce many of the atrocious things he experienced. Dix continued his painting study at the Dresden Academy of Art after the war under Otto Gussman and Max Feldbauer. Dresden was a shell of its former self in the post-war years. It was no longer a seat of power, and it saw a significant reduction in income and harsh rationing.

The artistic community, on the other hand, adapted and returned in full force. Dix was compelled to innovate as the value of the currency and political ideals fluctuated. During the war years, he had already included parts of Cubism and Futurism into his works; now, he began incorporating Expressionist as well as Dadaist components into his art.

He co-founded the Dresdner Sezession Gruppe in 1919 and took part in two of their exhibits at the Galerie Emil Richter. He made bizarre portraiture and woodcuts, as well as collages and mixed media pieces.

Dix blended and modified these techniques into his own kind of realism after 1920. He created some of his most terrible paintings of sexual brutality, homicide, and brutality during the following five years. Skat Players (1920) is an instance of this horrific, yet touching artwork. He exhibited in Berlin and Dresden in 1921 before going to Düsseldorf in 1922. This move was significant because he began studying with new masters, Wilhelm Herbeholz, and Heinrich Nauen, and became a member of Johanna Ey’s art salon group.

Dix later Married Koch in 1923 and had three offspring, all of whom were portrayed on canvas during their childhoods. All through the 1920s, Dix was featured in several of Germany’s most important new art exhibits. Most crucially, he was featured in Neue Sachlichkeit, the 1925 show at the Kunsthalle Mannheim that provided its name to the style with which Dix would be eternally identified.

Neue Sachlichkeit arose from Expressionism but took on characteristics of the traditional and formal realism that was gaining popularity in France and Italy. It seemed more serious and lifelike than preceding styles, while it was no less scathing in the hands of painters like Grosz and Dix.

Some of the painters were known as Verists and could be hostile and caustic, while others were known as Magic Realists and are much less harsh. Dix was a Verist, and he used his portrait abilities to depict the depravity and immorality of Weimar society in works such as Metropolis (1928). Otto Dix’s The War (1932) is another famous work from this era. Otto Dix was elected to the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin in 1931.

In the same year, he had shows in Germany and New York. This fame was short-lived, unfortunately, as the Nazis began to persecute him, viewing his paintings as unethical. As a result, he was not permitted to show in Germany, but he visited Switzerland numerous times during the mid-1930s and took part in various exhibits there.

Dix managed to express himself while being compelled to serve the Nazi government’s Reich Chamber of Fine Arts in 1934. Adolf Hitler is portrayed as the epitome of Envy in Seven Deadly Sins (1933). He was sent to a remote outpost and used his artwork to depict the surrounding sceneries. Dix was detained in 1939 on suspicion of planning to assassinate Hitler, but the accusations were dismissed. At the end of the war, he was taken by the French and kept as a prisoner until 1946. He didn’t waste any time in completing a triptych for the jail camp church.

Dix resumed his work after returning to Germany, picking up where the war had left off. He continued presenting his works and started creating lithographs, as well as recording his combat experiences and their repercussions in his works.

Late Years and Death

Dix’s latter work is mostly concerned with post-war misery, religious analogies, and Scriptural settings. All through the 1950s and 1960s, he traveled extensively and displayed his work regularly. He was elected to several art academies in Berlin, Florence, and Dresden.

In 1965, he kept making prints and appeared in a mini-documentary film. After visiting Greece in 1967, he endured a stroke that immobilized his left hand. He passed away in 1969.

Legacy

Dix is most known for the portraits he created during the Weimar Republic, which helped create the persistent common image of that notoriously hedonistic period in German history. They also had a strong impact on portrait artists throughout the 20th century.

Despite the fact that the development of abstraction in the 1940s and 1950s eroded the prominence of representational portraiture, the legacy of portrait painting has endured across the West, and many major painters continue to speak highly of Otto Dix’s paintings.

Otto Dix’s Paintings

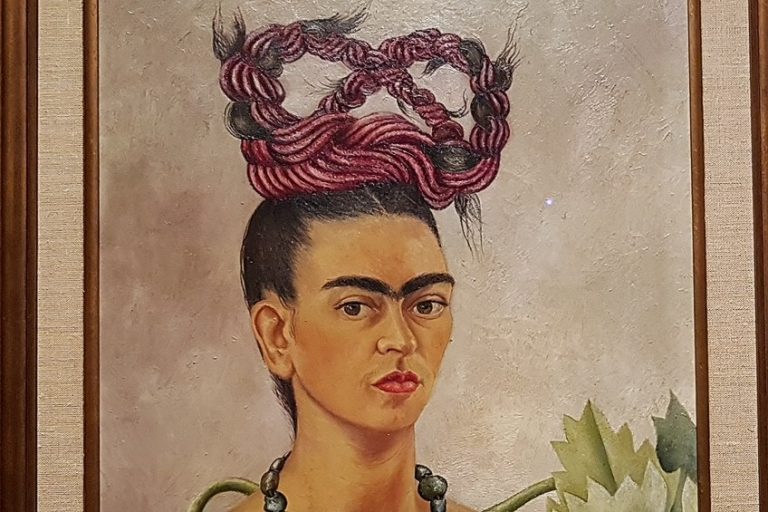

Otto Dix was first attracted to Dada and Expressionism, but, like many of his peers in Germany during the 1920s, he was influenced by developments in France and Italy to adopt a cold, linear drawing technique and more naturalistic images. Later, his style got weirder and more metaphorical, and he began to show naked women as witches or embodiments of sadness.

Dix’s propensity toward realism was always tempered by an equal leaning toward the weird and metaphorical. His depictions of prostitutes and maimed war veterans, for instance, serve as symbols of a society that has been physically and ethically destroyed.

Although Dix’s art is well-known for its sharp-eyed representation of the human form, his early obsession with injured veterans, as well as his use of parody, imply that he felt uneasy with glorifying the human body – and the victorious human spirit – in his works.

Skat Players (1920)

| Date Completed | 1920 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 87 cm x 110 cm |

| Current Location | Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie |

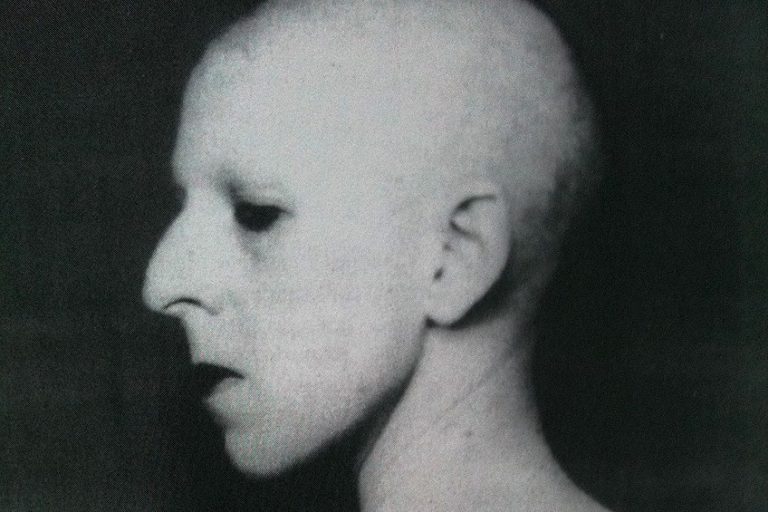

Three soldiers, scarred by World War I, are represented in this genre scenario playing a classic German card game at a Dresden café. A solitary wall lamp, newspaper poles with hooks, and a clothing rack surrounding them. These bodies are fragmented and disconnected, with awkward stances and purposefully hideous features. The armless man on the left is holding his cards with his toes, and the skin on his face has been deformed and destroyed by warfare. A telephone cable, a commonplace item, serves as a new ear, flowing down the side of his face as if entering his body.

The center figure is half-man, half-machine, with two wiry prosthetic legs and a patched face.

This is a picture of fractured bodies, representing a devastated nation after WWI. The guy on the right is still dressed in his outfit and Iron Cross, his hair neatly brushed, clutching to the nationalism that has led to his and his country’s demise. The fact that they are playing a card game is crucial; the guys play out the hand given to them by war and continue to play.

Dix used the recurrence of the chair legs, cards, and the men’s crippled extremities to create a work that is distressing in both form and substance.

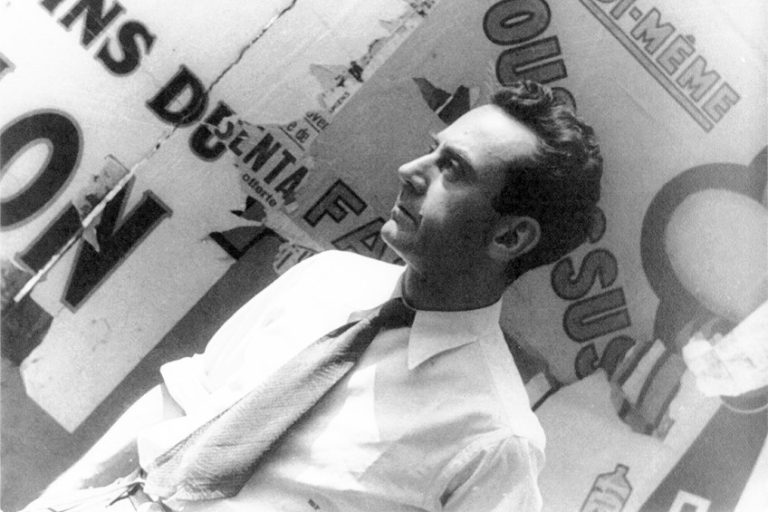

Portrait of the Lawyer Dr. Fritz Glaser (1921)

| Date Completed | 1921 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 106 cm x 79 cm |

| Current Location | Pompidou Center, Paris |

This picture is typical of Dix’s early 1920s portraiture, in which he painted his professional associates – physicians and other luminaries who were also interested in the arts. Dr. Glaser amassed a large art collection that included pieces by Klee, Kandinsky, and Nolde.

Dix depicts him standing in front of a destroyed facade of a typical ornate Dresden building.

The artist highlights the main characteristics of Glaser’s face, in this instance his Semitic nose, as is characteristic of his proclivity toward caricature. The image also exemplifies the various inconsistencies in Dix’s multiple works.

These inconsistencies were the cordial contacts he had with many of Dresden’s elite, and the scathing tone with which his artwork portrayed them.

The War (1932)

| Date Completed | 1932 |

| Medium | Oil on Wood |

| Dimensions | 204 cm x 102 cm |

| Current Location | Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden |

Otto Dix’s The War is a triptych with a predella panel beneath that depicts a historical painting amid a landscape. The story opens in the left panel, with troops in steel helmets leaving for battle through a dense haze, already condemned in Dix’s opinion.

An injured soldier is brought off the battlefield in the right panel, while the devastation of war is represented in the center panel.

This is a dismal and dreary world teeming with death and destruction, ruled over by a corpse. Trees have been burnt, and corpses have been bruised, ripped, and rendered dead. War has influenced every aspect of the terrain.

Otto Dix’s wartime experiences had a profound impact on him, and he returned to them frequently for inspiration.

Recommended Reading

Otto Dix, a German artist, is most known for his works of art depicting tormented, exploited human beings expressing the turbulence of his period. Maybe you would like to discover even more about his life and artworks. If so, check out this list of books that delve deeper into Ottos Dix’s paintings and biography.

Otto Dix (2010) by Olaf Peters

Otto Dix’s paintings are presented in this lavishly illustrated volume on the notorious German artist known for his honest depiction of life during wartime. Dix went on to produce many of the most stunning anti-war pictures of the current period. His art also contains disturbing portrayals of regular existence in the Weimar Republic after World War I. This book delves into Dix’s whole career, from his early expressionist works to his progressive acceptance of classically informed realism.

- Examines every aspect of Dix's career

- Generously illustrated monograph on the artist

- A number of his rarely seen landscapes are included here

Otto Dix and the First World War: Grotesque Humor, Camaraderie, and Remembrance (2019) by Michael Mackenzie

Famous for his superb portraits, Otto Dix was first enlisted in World War One before going on to become one of the most significant and influential artists of the Weimar era. Disturbed by his own first-hand experience of the war, Dix created incredibly difficult-to-understand, yet compelling artworks about what he had seen. Often, Dix’s works have been presented as a lone voice of reason in Germany between the two world wars. In this book, Dix and his artworks are placed firmly within the center of Weimar society.

That brings this look at the strange and wonderful works of Otto Dix to a close. In this article, we have discovered how Dix’s time spent as a soldier in WWI influenced his initial major themes, which included injured soldiers, such as in Otto Dix’s The War (1932) painting. Otto Dix’s paintings grew increasingly somber and allegorical in the early 1930s, and he became a target of the Nazis. As a consequence, he gradually shifted away from socioeconomic concerns, focusing on sceneries and theological themes instead.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Is Otto Dix?

Otto Dix is a ruthless satire in contemporary art. In the 1910s, when many artists had abandoned portraiture in favor of abstraction, Dix returned to the genre, including caustic caricatures into his depictions of some of Germany’s leading individuals. His other tale subjects are well-known for their denunciation of modern-day urban corruption and immorality.

What Kind of Art Did Otto Dix Produce?

Dix’s predisposition toward realism was always tempered by an equal leaning toward the weird and metaphorical. His depictions of prostitutes and maimed former soldiers, for instance, serve as representations of a civilization that is both materially and ethically wounded. Although Otto Dix’s paintings are known for their sharp-eyed depictions of the human figure, his early obsession with wounded soldiers and his use of caricature imply that he felt uncomfortable with honoring the human body in his works.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Otto Dix – Scathing Satirist of German Brutalities.” Art in Context. March 24, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/otto-dix/

Meyer, I. (2022, 24 March). Otto Dix – Scathing Satirist of German Brutalities. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/otto-dix/

Meyer, Isabella. “Otto Dix – Scathing Satirist of German Brutalities.” Art in Context, March 24, 2022. https://artincontext.org/otto-dix/.