Editorials

‘9’ – Revisiting the Stitchpunk Horrors of 2009’s Animated Movie

For the longest time, animation has been hindered by a misguided notion that animated movies are meant for kids. Sure, there have always been popular outliers like the infamous Fritz the Cat and 1981’s Heavy Metal, but it was only recently that animation began to be legitimized by the industry at large (even if that’s mostly due to a handful of auteurs like Guillermo del Toro publicly defending animation as a medium instead of a genre).

Unfortunately, this means that plenty of edgier animated projects ended up slipping through the cracks over the years, with general audiences usually favoring family-oriented entertainment over experimental stories dealing with more mature themes. One such project is Shane Acker’s underrated 2009 thriller 9, a post-apocalyptic adventure that deserved more attention and pushed its PG-13 rating to the absolute limit.

Originally an Oscar-nominated short film that Acker developed while studying at UCLA, the first version of 9 caught the attention of both Tim Burton and Russian producer Timur Bekmambetov, who were enthralled with the film’s unique setting and design. This unlikely duo of Hollywood titans would then give Acker the chance to expand his 11-minute short into a feature-length project that would replace the eerie silence of its source material with a celebrity voice cast.

A few years of hard work later led to the release of Focus Features’ 9, a dark animated film that follows the youngest of a group of living ragdolls (Elijah Wood) as he embarks on an epic journey through a post-apocalyptic wasteland overrun by mechanical abominations. Along the way, the inquisitive doll slowly uncovers the horrible secret behind the current state of this ruined world and the alchemical origin of his fellow “Stitchpunks.”

It will probably come as no surprise that this strange little film wasn’t the resounding success that Burton and Bekmambetov were hoping for, with 9 only barely raking in a profit at the box office while also garnering a mixed reaction from critics. At the time, reviewers complained that the movie’s shallow narrative didn’t quite match its evocative visuals while also unfavorably comparing it to other dark animated classics.

In fact, the flick ended up being overshadowed by another Focus Features production that came out that very same year, which was Henry Sellick’s beloved adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s Coraline.

SO WHY IS IT WORTH WATCHING?

Looking back on the film 14 years later, it’s pretty clear that the cheap 3D animation hasn’t aged all that well, with muddied textures and simple rigging that often look more like a contemporary videogame than a big budget animated film – and that’s not even mentioning the less-than stellar script that doesn’t quite live up to the lofty ambitions of the film’s premise.

However, the sheer artistry behind the picture continues to stand out in spite of all these flaws, and the benefit of hindsight allows us to appreciate 9 even more due to the fact that we haven’t really seen anything in animation that feels remotely like this movie since it first came out. Admittedly, almost all of these unique qualities are limited to the film’s visuals, but that doesn’t make them any less impressive.

In fact, the consistently gorgeous designs and moody atmosphere make this a perfect hangout movie, and I’d argue that it can be even more enjoyable as an engaging piece of background entertainment than as a proper narrative experience. I mean, the Danny Elfman score on its own is already worth the price of admission, and Acker makes the most of his celebrity ensemble by giving nearly every character a distinct personality to go along with their high-profile voice talent (which ranges from Crispin Glover to Jennifer Connelly).

That’s why I think it’s a huge shame that this ended up being the director’s only feature-length production, as I would have loved to see what other bizarre animated worlds Acker could have come up with had this film been successful – especially if his future projects could have secured a larger budget.

WHAT MAKES IT HORROR ADJACENT?

9 is certainly darker and grittier than your average 3D animated film, featuring some disturbing imagery and touching on several adult themes, but it’s still not quite a proper horror film. Despite its grim setting, the movie focuses on a traditionally fantastical adventure as this rag-tag group of hand-stitched misfits is forced to work together in order to overcome the dark forces that have taken over the earth.

That being said, the film boasts a menagerie of bio-mechanical horrors that wouldn’t feel out of place in an Army of Frankenstein sequel, with plenty of terrifying chase sequences even a number of brutal death scenes that are likely to shock younger audiences who are only used to Disney-style action. 9 also refuses to shy away from the horrors of fascism, with the Third-Reich-inspired dictatorship that resulted in the apocalypse suggesting that this was a terrifying world long before the machines took over and began exterminating human beings.

Of course, it’s the aforementioned mood that really sells the picture for me, with the gloomy environments and curious art direction making the entire movie feel like a memory from a fleeting nightmare, complete with cybernetic monsters decorated with skulls and a surreal combination of science and magic.

The film would probably have stood the test of time better had it been a stop-motion endeavor like Acker had originally intended (though that would likely have resulted in even bigger losses for the studio) and I wish that the script had been more thoroughly polished before the producers settled on a final draft, but I still think that 9 is an inspired example of apocalyptic fiction and might even work as a piece of gateway horror for younger viewers.

There’s no understating the importance of a balanced media diet, and since bloody and disgusting entertainment isn’t exclusive to the horror genre, we’ve come up with Horror Adjacent – a recurring column where we recommend non-horror movies that horror fans might enjoy.

Editorials

Seeing Things: Roger Corman and ‘X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes’

When the news of Roger Corman’s passing was announced, the online film community immediately responded with a flood of tributes to a legend. Many began with the multitude of careers he helped launch, the profound influence he had on independent cinema, and even the cameos he made in the films of Corman school “graduates.”

Tending to land further down his list of achievements and influences a bit is his work as a director, which is admittedly a more complicated legacy. Yes, Corman made some bad movies, no one is disputing that, but he also made some great ones. If he was only responsible for making the Poe films from 1960’s The Fall of the House of Usher to 1964’s The Tomb of Ligeia, he would be worthy of praise as a terrific filmmaker. But several more should be added to the list including A Bucket of Blood (1959) and Little Shop of Horrors (1960), which despite very limited resources redefined the horror comedy for a generation. The Intruder (1962) is one of the earliest and most daring films about race relations in America and a legitimate masterwork. The Wild Angels (1966) and The Trip (1967) combine experimental and narrative filmmaking in innovative and highly influential ways and also led directly to the making of Easy Rider (1969).

Finally, X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes (1963) is one of the most intelligent, well crafted, and entertaining science fiction films of its own or any era.

Officially titled X, with “The Man with the X-Ray Eyes” only appearing in the promotional materials, the film arose from a need for variety while making the now-iconic Poe Cyle. Corman put it this way in his indispensable autobiography How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime:

“If I had spent the entire first half of the 1960s doing nothing but those Poe films on dimly let gothic interior sets, I might well have ended up as nutty as Roderick Usher. Whether it was a conscious motive or not, I avoided any such possibilities by varying the look and themes of the other films I made during the Poe cycle—The Intruder, for example—and traveling to some out-of-the-way places to shoot them.”

Some of these films, in addition to Corman’s masterpiece The Intruder (1962), included Atlas and Creature from the Haunted Sea in 1961, The Young Racers (1963), The Secret Invasion (1964), and of course X, which was originally brought to him (as was often the case) only as a title from one of his bosses, James H. Nicholson. Corman and writer Ray Russell batted the idea presented in the title around for a couple days before coming to this idea also described in Corman’s book:

“He’s a scientist deliberately trying to develop X-Ray or expanded vision. The X-Ray vision should progress deeper and deeper until at the end there is a mystical, religious experience of seeing to the center of the universe, or the equivalent of God.”

While Corman worked on other projects, Russell and Robert Dillon wrote the script, which has a surprising profundity rarely found in low-budget science fiction films of the era. Like The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957) before it and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) after, X grapples with nothing less than humanity’s miniscule place in an endless cosmos. These films also posit that, despite our infinitesimal nature, we still matter.

In some senses, X plays out like an extended episode of The Twilight Zone. Considering Corman’s work with regular contributors to that show Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont during this era, this makes a lot of sense. It begins with establishing the conceit of the film—X-ray vision discovered by a well-meaning research scientist Dr. James Xavier, played by Academy Award Winner Ray Milland. The concept is then developed in ways that are innocuous, fun, or helpful to humanity or himself. As the effect of the eyedrops that expand his vision cumulate, Xavier is able to see into his patients’ bodies and see where surgeries should be performed, for example. He is also able to see through people’s clothes at a late-evening party and eventually cheat at blackjack in Las Vegas. Finally, the film takes its conceit to its extreme, but logical, conclusion—he keeps seeing further and further until he sees an ever-watching eye at the center of the universe—and builds to a shock ending. And like many of the best episodes of The Twilight Zone, X is spiritual, existential, and expansive while remaining grounded in way that speaks to our humanity.

Two sections of the film in particular underscore these qualities. The first begins after Xavier escapes from his medical research facility after being threatened with a malpractice suit. He hides out as a carnival sideshow attraction under the eye of a huckster named Crane, brilliantly played by classic insult comedian Don Rickles in one of his earliest dramatic roles. At first, a blindfolded Xavier reads audience comments off cards, which he can see because of his enhanced vision. Corman regulars Dick Miller and Jonathan Haze appear as hecklers in this scene. He soon leaves the carnival and places himself into further exile, but Crane brings people to him who are infirmed or in pain and seeking diagnosis. Crane then collects their two bucks after Xavier shares his insights. This all acts as a kind of comment on the tent revivalists who hustled the desperate out of their meager earnings with the promise of healing. Now in the modern era, it is still effective as these kinds of charlatans have only changed venues from canvas tents to megachurches and nationwide television.

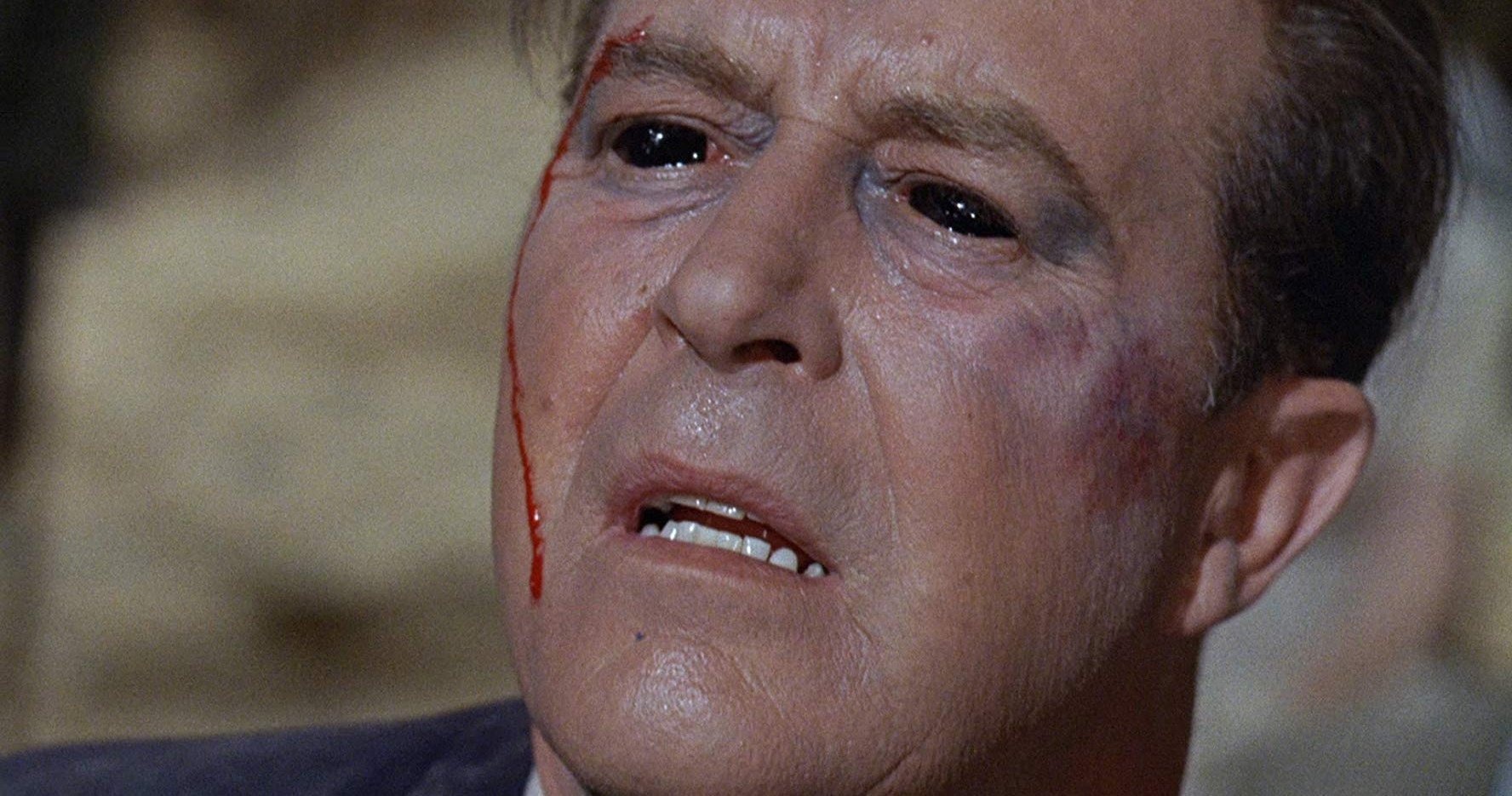

The other sequence comes right at the end. After speeding his way out of Las Vegas under suspicion of cheating at cards, Xavier gets in a car accident and wanders out into the Nevada desert. He finds his way to a tent revival and is asked by the preacher, “do you wish to be saved?” He responds, “No, I’ve come to tell you what I see.” He speaks of seeing great darknesses and lights and an eye at the center of the universe that sees us all. The preacher tells him that he sees “sin and the devil,” and calls for him to literally follow the scripture that says, “if your eye causes you to sin, pluck it out.” Xavier’s hands fly to his face, and the last moment of the film is a freeze frame of his empty, bloody eye sockets.

At this point, Xavier is seeing the unfathomable secrets of the universe. Taken in a spiritual sense, he is the first living human to see the face of God since Adam before being exiled from the Garden of Eden. But neither the scientific community nor the spiritual one can accept him. The scientific community sees him as a pariah, one who has meddled in a kind of witchcraft because he has advanced further and faster than they have been able to. The spiritual leader believes he has seen evil because he cannot fathom a person seeing God when he, a man of God, is unable to do so himself. The one man who can supply answers to the eternal questions about humanity’s place in the universe, questions asked by science and religion alike, is rendered impotent by both simply because they are unable to see. The myopia of both camps is the greater tragedy of X. Xavier himself perhaps finally has relief, but the rest of humanity will continue to live in darkness, a blindness that is not physical but the result of a lack of knowledge that Xavier alone could provide. In other words, he could help them see, or to use religious terminology, give sight to the blind. Rumor has it that a line was cut from the final film in which Xavier, after plucking out his eyes, cries out “I can still see!” A horrifying line to be sure, but it also would have kept the tragedy personal. In the final version, the tragedy is cosmic.

I usually try to keep myself out of the articles in this column, but allow me to break convention if I may. Roger Corman’s death affected me in ways that I did not expect. With his advanced age I knew the news would come down sooner rather than later, but maybe a part of me expected him to outlive us all. Corman’s legacy loomed large, but he never seemed to believe too much of his own press. I’ve heard many stories over the years of his gentle, even retiring demeanor, his ability to have tea and conversation with volunteers at conventions, his reaching out to people he liked and respected when they felt alone in the world. I never had the pleasure of meeting or speaking with him myself, but I did get to speak with his daughter Catherine and sneak in a few questions about her father. It was fascinating to hear about the kind of man he was, the things that interested him, and the community he created in his home and studio.

X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes was the first Corman movie I ever heard of, though I saw it for the first time many years later. When my family first got a VCR back in the mid-80s, my parents quickly learned about my obsession with horror movies, though at the time I was too afraid to actually see most of them. One day while browsing the horror section at the gigantic, pre-Blockbuster video store we had a membership with, my dad said, “Oo! The Man with the X-Ray Eyes! That’s a great one.” For whatever reason, we didn’t pick the video up that day, but I never forgot that title. Then I read about it in Stephen King’s Danse Macabre and, though he spoils the entire movie in that book (which is fine, it’s not really that kind of movie) I was enthralled and became a bit obsessed with seeing it. Of course, by then it was a lot harder to track down the film, so I only had King’s plot description, a few scattered details from my dad’s memory, and my imagination to go by. When I finally did see it, the film did not disappoint. Sure, the special effects, clothes, music, and styles are pretty dated, but the themes and messages of the film are endlessly fascinating and relevant.

It may seem obvious, but X is a film about seeing and all the different meanings of that word. There are those things seen by the physical eye but there is so much more to it than that limited meaning. It asks questions of what we see with imagination, the spiritual, and intellectual eye. It explores what society does to people who can truly see. Some are deified while others are condemned and ostracized. And then there are those questions of if there is something out there that sees us. Is it a force of good or evil or indifference? Is there anything at all out there that looks for us as much as we look for it? It may just be a silly little low-budget science fiction film, but somehow X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes has the power to provoke thought and imagination in a way few films can. It may even have the power to help us see in ways we could only imagine.

In Bride of Frankenstein, Dr. Pretorius, played by the inimitable Ernest Thesiger, raises his glass and proposes a toast to Colin Clive’s Henry Frankenstein—“to a new world of Gods and Monsters.” I invite you to join me in exploring this world, focusing on horror films from the dawn of the Universal Monster movies in 1931 to the collapse of the studio system and the rise of the new Hollywood rebels in the late 1960’s. With this period as our focus, and occasional ventures beyond, we will explore this magnificent world of classic horror. So, I raise my glass to you and invite you to join me in the toast.

You must be logged in to post a comment.