ArtSeen

Bruce Nauman: Disappearing Acts

Bruce Nauman, Contrapposto Studies, i through vii,2015/16. Seven-channel video (color, sound, continuous duration), dimensions variable. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2018 Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo courtesy the artist and Sperone Westwater, New York.

New York

MoMAOctober 21, 2018 – February 18, 2019

New York

MoMA PS1October 21, 2018 – February 25, 2019

Some artists and exhibitions can be summarized into a set of statements, the fundamentals of the work distilled. Bruce Nauman: Disappearing Acts is not among those. Surveying the massive retrospective that spans MoMA’s midtown building as well as PS1 in Long Island City, however, the main challenge is surfeit. It is a stellar curatorial achievement long in the making. Helmed by Kathy Halbreich and aided by Magnus Schaefer and Taylor Walsh, all of MoMA; in collaboration with Heidi Naef and Isabelle Friedli of the Schaulager Basel, the retrospective brings together nearly 170 works spanning painting, drawing, architectural assemblages, sculpture, installation, light, sound, and the moving image (film and video) from Nauman’s decades-long career. Just about a third of the exhibition is installed on the sixth floor of MoMA, while the majority is at PS1 in Long Island City. The curators have framed the exhibition more or less chronologically along thematic lines of creative withdrawal and corporeal disappearance. While this provides some welcome guidance, any attempt to categorize often ends up underscoring how the artist’s work continually spills over, resisting even the most generous attempts.

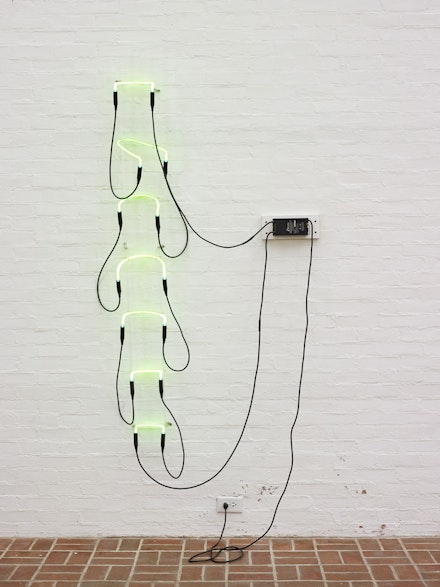

Bruce Nauman, Neon Templates of the Left Half of My Body Taken at Ten-InchIntervals, 1966. Neon tubing with clear glass tubing suspension frame, 70 x 9 x 6 inches. © 2018 Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Andy Romer Photography. Courtesy the Glass House, a site of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Chronological overviews of Nauman’s career typically fail to satisfy. The seventy-seven year old artist, who has since 1979 stayed mostly off the artworld radar in New Mexico, briefly flirted with abstraction before moving on to a Minimalism-inflected sculptural practice. This was the mid-1960s, which makes such a move par for the course. But where Minimalism favored a vocabulary of seriality and near-clinical precision, Nauman’s works from this period are rough-hewn and markedly scaled down. Even in these early years, the artist’s concern with the physicality of the body is plainly evident. Neon Templates of the Left Half of My Body Taken at Ten-Inch Intervals (1966) at first glance resembles a simple cross-section of mammalian vertebrae, its seven wall-mounted neon tubes brackets crudely approximating, perhaps, the serial automatism of a Donald Judd wall piece (though the mess of wires limits such comparisons). A closer look reveals its semiotic operation: as signifier, it recalls in form and in scale the materiality of the body that precedes it; yet what is signified is the body’s absent presence. Call this the Wittgensteinian Nauman, perhaps––enamored already with the relations between word and image, and therefore concept and material, that would continue to inform his work through subsequent decades.

Nauman quickly realized that bodily autonomy is rarely without context; rather, it is continually mediated: socially, environmentally, and by means of media technologies. 1972’s Kassel Corridor: Elliptical Space, originally created for Documenta 5 and infrequently shown afterward, comprises a nearly fifty-foot long corridor with a locked door where visitors are permitted entry––keys are handed out one at a time––for an hour’s duration. You may welcome the unexpected privacy in the midst of an exhibition that draws crowds every day, but that sense of privacy swiftly turns to unease when you realize both ends of the corridor are open to the gaze of visitors gathered around the work. You have become the center of attention, exposed to a public gaze even as you are physically constrained within a narrow space. Antinomies of privacy and publicity are at play here, and there is no resolution at hand. The nearby Going Around the Corner Piece from 1970, with cameras installed such that the spectator’s own body is thrown back––in estranged fashion on video monitors––to their gaze, presents further variations on visual and technological mediations on the body as it negotiates built environments.

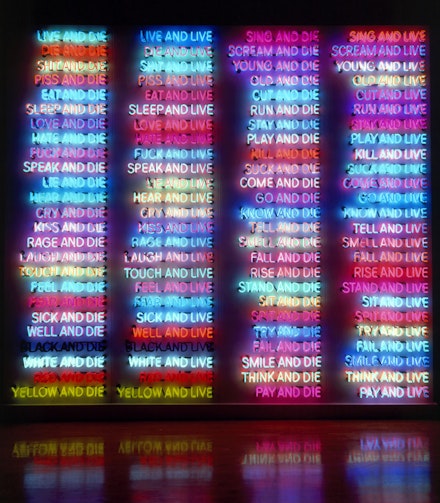

Bruce Nauman, One Hundred Live and Die, 1984. Neon tubing with clear glass tubing on metal monolith, 118 x 132 1/4 x 21 inches. © 2018 Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Dorothy Zeidman. Courtesy the artist and Sperone Westwater, New York.

The “disappearing acts” alluded to in the show’s title, and discussed extensively in the catalogue, reiterate the commonly held view that Nauman’s later works mark a “disappearance” or withdrawal of the artist’s body. Gone are the oppressive, near-paranoid setups that entrap the body, subjecting it to a surveillant gaze or otherwise producing claustrophobic effects. In their place are works made of sound and light, usually neon. Such is the case, for instance, in One Hundred Live and Die (1984). This imposing work, with its bright colors and vertical format, has become an Instagram favorite from the show. It recognizably builds on Nauman’s early fascination with language, as the grid of phrases (“Cry and die,” “Touch and live,” “Smile and die,” “Pay and live”) lights up in different combinations. The words are not all threatening, necessarily, but their presentation is just psychotic enough to leave us apprehensive: what does it mean when an artwork appears to treat kissing and living just the same as kissing and dying?

The body is likewise not apparent in my favorite work in the show: Days (2009), a work that takes up most of an enormous, brightly-lit room as one finds one’s way toward the exit. Here, fourteen ultra-thin speakers remain suspended roughly at head-height, forming a corridor through the space. Each pair emits a different voice that repeats, monotonously and in randomized order, the days of the week. It seems to me that Days, emerging from Nauman’s later-career output, adroitly sidesteps the flashy, in-your-face presentation of his neon works while retracing lines of thinking about the body, presence, and their technological mediation from the artist’s earliest years. Sublimating as it does the substance of the work into thin air, Days is at once everywhere and nowhere in that room.

And yet I’d suggest the body continues to be central to the concerns of both works, emerging as they do across twenty-five years. It is true that Nauman’s early strategies––putting the obdurate physicality of the body front and center––quickly gave way to works in which such physicality is no longer immediately perceptible. It is crucial to keep in mind, however, that Nauman’s focus even in the early works was never quite the body on its own terms but about the ways in which the body comes to be constituted. One Hundred Live and Die, in its individual statements and in the multiplicity of its combinations, is a statement of entire lives lived: feeling, screaming, raging, laughing, trying. At the moments when the entire work comes ablaze with neon light, it’s hard not to be struck at its sheer imaginative scope: all those verbs (“eat,” “sleep,” “fuck,” “cry,” “touch,” “play”…) that constitute the process of living. The open-ended generosity of One Hundred Live and Die both acknowledges, and arguably inverts, popular advertising’s love of using neon signage and pithy slogans to promote blunt consumerist messages. In Days, a somewhat similar relay of temporality and signification is set in motion as one moves through the virtual corridor of sound. Just as the arbitrary combinations of living and dying, variously illuminated, gesture toward the fullness of lived experience, the randomized enunciation of weekdays come to confuse the passage of time even as you physically pass through the work. There are few things that mark the quotidian passage of a life as simply, as inexorably, but also as repetitively, as a Monday turning into a Tuesday into a….

Bruce Nauman, Myself as a Marble Fountain, 1967. Ink with wash, 19 x 24 inches. © 2018 Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Kunstmuseum Basel, Martin P. Bühler.

The truth is, the centrality of the body in Nauman’s work is ever-present and oriented around a very particular body: white and male. An ink drawing work from 1967, Myself as a Marble Fountain, emphasizes this. It’s a sketch of the artist as a sculpture, water gushing from its mouth––the whole quite clearly evoking the tradition of figural fountains in classical Western sculpture. That’s not to say there aren’t other allusions involved: one thinks, too, of Duchamp’s Fountain (1917). In fact, (self-) identification with fountains recurs in Nauman’s work across various photographs, drawings, and sculptures. Contemporary decolonial enthusiasm sometimes lumps white male bodies into a singular, undifferentiated unit, namely the colonizing, patriarchal figure that is the architect of an unequal modernity. It’s worth lingering, therefore, on a series of Nauman’s works that undercuts such a line of criticism and ruthlessly implicates the white male body within time––and therefore within specific historical formations. The white male body of the Enlightenment that imagined itself as both source of, and exempt from, historical modernity is revised here as radically contingent, its hegemonic grasp tenuous at best.

Walk with Contrapposto (1968) is an early Nauman work in which the artist fashioned a narrow corridor and then filmed himself walking along its confining space with wildly exaggerated movements, hips swinging freely. The work’s title, and Nauman’s physical motions, clearly evoke the poses of the idealized male figure so recurrent in European classical sculpture. (One might note, too, that the sheer campiness of Nauman’s bodily movements ends up queering this relation.) Decades later, Nauman returned to this work in Contrapposto Studies, i through vii (2015/16) and Contrapposto Split (2017). The Studies are a number of digital projections showing the artist (attempting to) re-perform the old motions. But the images are heavily distorted, pixelated and shown both in positive and negative forms. The flat digital images are often horizontally sliced into pieces. Contrapposto Split shows the artist carefully walking toward the camera even as the top and bottom segments of his body veer off in uneven directions. If the original work consciously evoked the tradition of the eternal masculine ideal (at least as European classicism once imagined it), it also questioned the validity of that tradition. Decades later, Nauman leaves us in no doubt: there is no trace of idealism here, nor any claims on eternity. The effects of old age, as much as that of technological manipulation of the image, reveal the white male body––and the power it historically claimed for itself––to be all too transient.