Art Books

Hundertwasser For Future

An impressive sampling of Friedensreich Hundertwasser’s manifestos, speeches, and writings, published in English for the very first time.

Hundertwasser For Future

(Hatje Cantz, 2020)

Friedensreich Hundertwasser (1928 - 2000) had many ideas for the future, an impressive sampling of which is now available in a compact new volume from Hatje Cantz. Hundertwasser (born as Friedrich Stowasser), painter, architect, ecological activist, and sometimes-philosopher, is known for his curvilinear buildings in Vienna, and distinctive brightly-colored paintings, often described as “kitschy.” (In a 1981 speech, Hundertwasser pronounced that “The absence of kitsch makes our life unbearable.”) Hundertwasser for Future compiles selections from his various manifestos, speeches, and writings, published in English for the very first time, alongside some of his paintings and designs from his long and varied career.

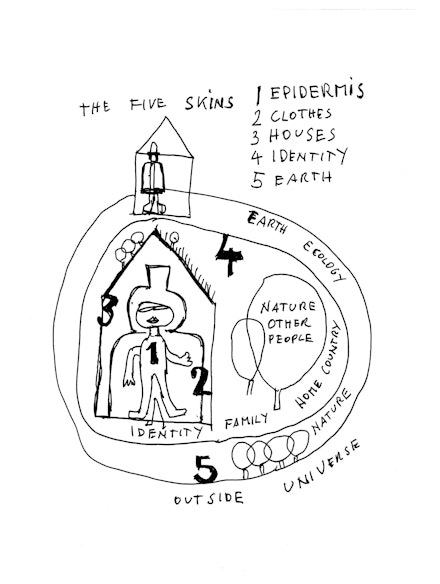

Hundertwasser’s words are organized in chapters according to a pictogram of Man’s Five Skins: The Epidermis, The Clothes, Man’s House, The Social Environment and Identity, and The Global Environment—Ecology and Mankind. This organization thematically orders his thoughts, quotations, drawings, and plans, resulting in an anecdotal approach, sparing context or background (there is one short introductory essay and one concluding essay, arguing for an increased awareness of the artist’s genius).

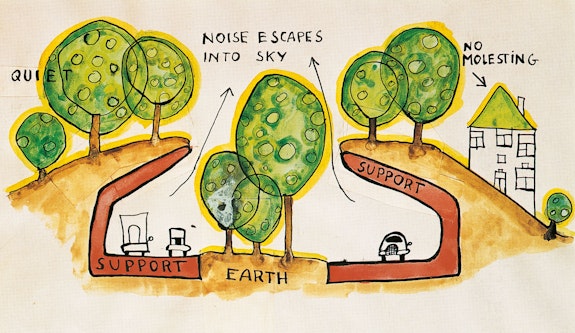

Hundertwasser did a stint at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, and spent the 50’s with the freethinking postwar kids. By 1959 he realized he did not need money or belongings, and bounced around Europe, until settling into a self-sufficient farm in New Zealand in the 1970s. He worked as an “architecture doctor,” hoping to remodel “sick” buildings and designs. He theorized a “tree tenant,” a tree that grows out of a window attached to the building’s façade and pays “rent” by providing beauty and oxygen, and touted this design as the epitome of architecture-improvement in several speeches and writings in the 70s and 80s. He designed an “eye-slit house,” a home built into the side of a hill surrounded by greenery that appears from a distance like a human face (a photograph of a 1974 built model is included in the book). He made his clothes of natural or recycled materials and had a special fondness for tall hats. His diet consisted almost entirely of wild nettles. He was fanatic about toilets. He was against drug use (because, as he mentioned in his 1967 public “Speech in Nude for the Right to a Third Skin,” drug users “live in a dream”). He thought Pollock and Raushcenberg were wasteful and preferred to paint frugally and recycle materials obsessively.

In his life and career, Hundertwasser pursued a synthesis between ambitious green expansion, and a life of moderation and self-sufficiency. He created in accordance with his moral ambition. Consider the humus toilet, which is referenced often in this collection. Composting toilets become a staple of the artist’s life and activism, as he often invoked their simple perfection as a best example for the wonderful ease and possibility of living in accordance with nature. He published a toilet manifesto, “The Sacred Shit—The Shit Culture” in 1980, exploring his commitment to humus toilets, and by that point was already relying on the technology at his farm in New Zealand. Hundertwasser’s humus toilet is at once a useful tool, manifesto incarnate, natural marvel, and work of art. There was no distinction between living and art-making.

Hundertwasser For Future leaves a reader with more questions than answers, introducing ideas without ever really explaining their source or scope. It’s a frustrating read, then, as it is an enlightening one, doing a disservice to Hundertwasser’s intellectual power while sharing the singular pleasure of his one-of-a-kind insight with a wider English-speaking audience. Depth is sacrificed for breadth, a cost worth accepting for the chance to glimpse at the artist’s vision for a greener new world.

Make no mistake: this man—who spoke and created from a limited point of view—does not have the antidotes to all of our ailments. Nonetheless, the overwhelming result by the end of Hundertwasser For Future is an unparalleled experiment in creative problem-solving. He said, after all, “no building is so sick that it cannot be healed,” and one gets the sense that he sincerely meant it. In the 1967 public Speech in Nude for the Right to a Third Skin, he guaranteed he could “transform the city of Munich in five hours in a way that you wouldn’t recognize it.” The tragedy at hand is how little has changed. In his 1968 manifesto “Loose from Loos” (criticizing the oppressive straight lines of Adolf Loos), Hundertwasser wrote that he was absolutely sure, in just a few years, building ordinances would require that every building have a layer of earth on the roof and four stories of forest for each story of human living. What year, exactly, will that be? He didn’t say.