You could say that Helene Schjerfbeck (1862–1946) became an artist at the age of four, after falling down the stairs and breaking her hip. During her recovery, her father Svante gave her a pencil, and she started to draw.

When Helene was just 13, Svante died. Her mother Olga was left to raise two children alone.

Helene Schjerfbeck won a scholarship to the drawing school of the Finnish Art Society at just 11, making her the school’s youngest student ever.

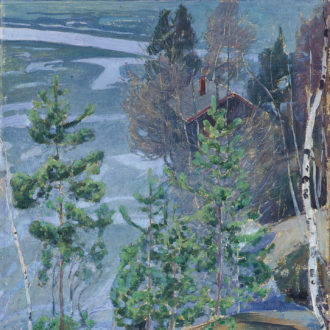

Looking outward

Schjerbeck painted Cypresses, Fiesole in 1894. Fiesole is a location near Florence, Italy.

Photo: Hannu Aaltonen/Ateneum Art Museum/Finnish National Gallery

Upon graduating, she desperately wanted to go to Paris, but was too young to travel alone. Instead, she stayed in Helsinki, studying French plein-air realism under Adolf von Becker.

At 18 years old, Schjerfbeck finally made it to Paris, on a travel grant from Finland’s Senate. She spent much of the next decade travelling, connecting with artistic communities in Brittany, Florence and Saint Ives in Cornwall.

Unlike many of her contemporaries, Schjerfbeck was not a national romanticist. Instead, she took inspiration from the visual culture of her time, including fashion, magazines and catalogues, and became an important figure in the early modernist movement.

Exhibitions get wide coverage

The Family Heirloom (1915–16) shows that Schjerfbeck took inspiration from the visual culture and fashions of her time.Photo: Yehia Eweis/Ateneum Art Museum/Finnish National Gallery

In 2019 and early 2020, London’s Royal Academy of Arts and Helsinki’s Ateneum Art Museum collaboratively organised back-to-back Schjerfbeck exhibitions. The Royal Academy put on a retrospective entitled simply Helene Schjerfbeck, introducing her to a wide British audience and prompting The Economist to write, “Unless you’re Finnish, you probably won’t have heard of this enigmatic artist. Here’s why she matters.”

Ateneum’s exhibition, called Through my travels I found myself, focused on Schjerfbeck’s time in Saint Ives and the inspiration she drew from contemporary fashion. “Finnish audiences already know Schjerfbeck, so we had to do something different,” says exhibition curator Anna-Maria von Bonsdorff.

“It had been seven years since we put on a Schjerfbeck exhibition,” she says. “Since so many of her works are abroad, in places like Japan and Germany, we only had [relatively] few of her paintings here. We were receiving feedback almost weekly that we should be displaying more of her work.”

Record visitor numbers

Mother and child (1886), by Helene Schjerfbeck, formed part of Through my travels I found myself, an Ateneum exhibition that broke the museum’s record for average daily attendance. Photo: Hannu Pakarinen/Ateneum Art Museum/Finnish National Gallery

The Ateneum exhibition averaged 3,102 daily visits, the highest daily visitor count in the museum’s history, for a total of 186,112 people between November 15, 2019 and January 26, 2020. By comparison, their 2009–10 Picasso exhibition averaged 2,835 people per day, although it lasted two months longer and amounted a greater total visitor tally.

The Royal Academy exhibition was popular, too. The catalogue became the third-best seller in the museum’s history, which von Bonsdorff hopes may help curators find three missing Schjerfbecks that are thought to be somewhere in the UK.

Bold and talented

The film Helene, starring Laura Birn and Johannes Holopainen, covers a period of Schjerfbeck’s life when she spent time with Einar Reuter. Photo: Nordisk Film

Schjerfbeck is believed to have fallen in love twice: once with an artist whose identity remains unconfirmed, and once with Einar Reuter, who later became her biographer. The second love story is the focus of Antti J. Jokinen’s 2020 film Helene, based on Rakel Liehu’s 2003 novel of the same name.

Jokinen’s artistic license includes filming the drama in Finnish, despite Schjerfbeck having been a Swedish-speaking Finn. (Swedish and Finnish are both official languages in modern Finland.)

The movie paints a picture of a bold, talented and fiercely determined woman. Laura Birn, who plays Schjerfbeck, spent many months studying under artist Anna Retulainen to prepare for the role.

Art, love and friendship

Helene Schjerfbeck (Laura Birn) goes through moments of joy and despair in the film Helene. Photo: Nordisk Film

“I watched her paint, and she taught me how to hold a brush and work with colours,” Birn says. “We painted together and talked about art, Schjerfbeck, being a female artist, movies, acting and life. It was one of the most interesting preparation processes I’ve been through.”

Helene tells the story of Schjerfbeck’s ill-fated love affair with Reuter (Johannes Holopainen). He is 19 years younger than she is, and they eventually part ways. Though heartbroken, Schjerfbeck finds support in her friendship with artist Helena Westermarck (Krista Kosonen) and distracts herself with art, ultimately remaining friends with Reuter. She corresponded with him for the rest of her life.

“Before studying her, I had this image of a fragile artist in my head,” says Birn. “But instead, I found her to be a passionate, obsessive, curious, ambitious, dramatic person with a dry sense of humour.”

A renewed following

Curators often show Schjerfbeck’s self-portraits together if possible. These four and others appeared at Ateneum’s exhibition Through my travels I found myself. Photos: Self-portrait (1884–85), Henri Tuomi; Self-portrait (1912), Hannu Aaltonen; Self-portrait with Red Spot (1944), Henri Tuomi; Self-portrait, en face I (1945), Hannu Pakarinen; all from Ateneum Art Museum/Finnish National Gallery.

Active as an artist for almost seven decades, Schjerfbeck is perhaps best known for her self-portraits. She painted around 40 of them, covering her life from youth to old age. “It is globally exceptional that she painted so many,” says von Bonsdorff.

Schjerfbeck has often been overshadowed by her male counterparts, such as Akseli Gallen-Kallela. But recently something has changed. “She has something to offer new audiences,” says von Bonsdorff. “She seems somehow contemporary. Her use of popular materials appeals to younger audiences.”

She has gained a renewed following. “Ten years ago, Schjerfbeck wasn’t really considered [Finland’s] number one painter,” says von Bonsdorff, “but now she really is.”

By Tabatha Leggett, July 2020

Helene Schjerfbeck paintings form part of the permanent collections of the Ateneum Art Museum and Villa Gyllenberg in Helsinki; the Gösta Serlachius Museum in Mänttä, central Finland; and the Turku Art Museum in southwestern Finland.