If this were Through The Keyhole, though, you’d be hard pushed to guess that this place belonged to a musician. The apartment that the silver-haired Geldof shares with his actor wife Jeanne Marine is a homely haven piled high with hundreds of books but few visible records. On the coffee table, you notice two hardbacks – Michel Houellebecq’s Serotonin and Vasily Grossman’s sprawling historical novel, Stalingrad. Russian history is a source of fascination for the frontman of the re-formed Boomtown Rats. His favourite TV programme of 2019 was Chernobyl.

The bleak locations of Craig Mazin and Johan Renck’s acclaimed factual drama were, for him, all too reminiscent of the Ireland where he grew up.

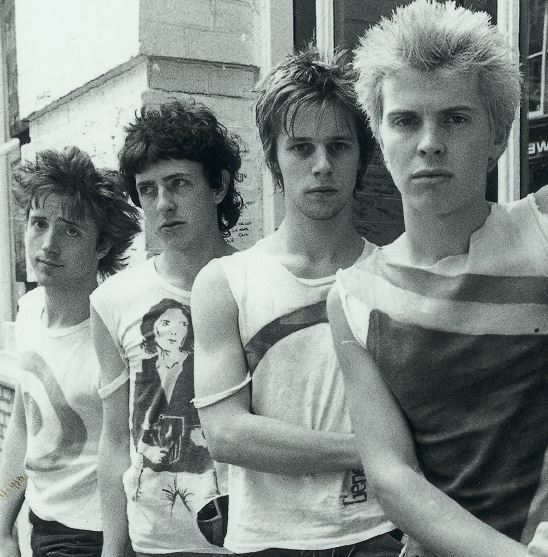

Though the London-centric received wisdom telling of punk history tends to underplay the importance of The Boomtown Rats, the fact is that Geldof and his band played a demonstrable part in modernising the Ireland of his youth. Why, in 1977, they even had their own Bill Grundy moment when they were invited back home for their first ever live television performance. Hosted every Friday by the universally revered Gay Byrne, The Late Late Show was second only to church on Sunday as the weekly event in which all of Ireland participated.

For Geldof, this symbolic acceptance by this televisual talisman of the status quo presented too good an opportunity. He knew that, among the viewers tuning in to watch him, were the priests at his alma mater, Blackrock College, who beat him so hard that he would frequently pray to his dead mother for deliverance; and Geldof’s father, who would end his own beatings with a hug – an act Geldof Jr described as a “pathetic act of hypocrisy” in his 1986 autobiography Is That It? And so, when the red light came on, Bob Geldof went in with both barrels: railing against the nuns in the audience and the pointless bodily denial they symbolised to his own father.

His life-long friend Bono said it was “the first time this world had been punctured by a voice from another generation”.

But, in January 2020, Bob Geldof – now, at 68, four years older than his father was at the time – fidgets uncomfortably at the memory. The day after the broadcast, his father – who had been watching the show at Dun Laoghaire Golf Club with an expectant throng of fellow members – simply said to him, “You hurt me very much.”

So much has changed since that moment, and most of it a matter of very public record. In 1978, as per his prediction on The Late Late Show, The Boomtown Rats enjoyed the first of their two chart-topping singles.

In 1984, after hectoring every A-lister into a recording studio to cut Do They Know It’s Christmas? and riding that momentum into the following year’s Live Aid concert, he became the reluctant face of famine relief.

He has had to negotiate unimaginable grief – losing both his ex-wife Paula Yates in 2000 and their daughter Peaches in 2014, both to heroin overdoses. The latter is powerfully addressed on the new Boomtown Rats album, Citizens Of Boomtown, with two beautiful new songs, Passing Through and Here’s A Postcard. And, indeed, the Rats – both their legacy and their return – is the subject that most instantly animates our wiry host. There’s just four of them this time around. “Johnnie [Fingers, pianist] is in Japan making his own music, but the door remains open,” says Geldof of his pyjama-attired pianist. “But it’s still audible, unmistakably us, don’t you think?”

In conversation, he’s surprisingly soft-spoken. Plenty of eye contact is made. Lengthy pauses greet some questions, especially the ones about Paula and Peaches. But the longest of all – 23 seconds – comes when I ask him whether he considers himself a good listener.

“I would like to be,” he says. “But I keep interjecting.”

When some bands re-enter the studio after decades apart, they sound like an older, wiser version of their earlier incarnation. But Citizens Of Boomtown is, with a couple of notable exceptions, a riotous affair. A good-time record.

I was asked early on by someone, “Why did you want to [re-form]?” And I said, “Curiosity, vanity and cash.” That was a bit of a smart-arse answer. But here’s the thing. You say it sounds like we’re having fun. Well, the first time around, it wasn’t much fun. We were living in a shared house in Chessington being woken up in the middle of the night by fucking emus. We had no money for ages. The struggle to get there is so intensive and focused, and you don’t know if you’re any good. It’s, “Here’s the next thing, and then the next…” and so on. And you’re just on this treadmill. So yeah, it’s more fun now, by a million miles.

Exactly. Our big driving impetus at first was to get out of Ireland. Nobody in the UK [music industry] paid any attention to Ireland, and we arrived just as all those other punk bands were arriving. I remember going into the offices of United Artists. They listened to the [demo] tape, and they said, “We’d give you a shot, but we just signed a band called The Stranglers yesterday.”

And so, we then went to Stiff, which was a new label – I was mad for that, because Dr Feelgood had paid for Stiff to be created, and they were our North Star, and also [because the label’s owner] Dave Robinson was a Paddy.

It would have been a great fit. When we played the tape, Dave was reading the NME and I grabbed it. I said, “Don’t fucking read when we’re playing our stuff!” And he goes, “Give it a rest, will you, I’m listening.” Anyway, they said they’d put out the demo tapes as an EP, but I thought the demos were fucking awful, so that was that. As we were leaving, the door opens and Dave says, “Oh, here’s that Declan guy I was telling you about: Declan, this is Geldof. We’re changing his name to Elvis [Costello].”

It focuses you. We had to have hits. Nigel Grainge [founder of Ensign] said to me after Mary Of The 4th Form [which reached No 15], “If you don’t get in the Top 10 with the next record, it’s over.” So, you’re told that and you’re there shitting yourself. The prospect of failure was deeply worrying to me. I was hugely anxious and self-doubting. If you listen to Wind Chill Factor from The Fine Art Of Surfacing [1979], which was written during those first days in London, it’s all in there: “It’s one of those days where I don’t like myself.”

I’ve always been uncomfortable with that song because it was a contrived attempt to write a hit. Also, Jonathan King said it was the only decent song I ever wrote – two very good reasons not to like it, then. But yeah, that was my first London song. In the summer of 1977, we had a party for Looking After No 1. Paula was there. She was wearing what I thought were sort of hippie clothes – a sort of lacey, early ’76 version of the ra-ra skirt, which was just beautiful. She looked so cool, like properly “hip”. She was with a couple of girls, and one of them I think was Magenta Devine. So, there were guys there who would later be in bands, like Richard Jobson. We felt like cunts, I gotta say.

We’re fresh off the boat, and there are these beautiful girls. I didn’t know that Paula had already gone into the record company to find out how she could meet me. Apparently, her mother had seen me on TV giving it plenty of lip, and she’d said to her, “He’s a very interesting boy.”

She actually used to say that! Miffed. “You never write a song about me!” and I’d say, ‘But love, you’re in there, you’re in there.’

Fall Down is definitely about her: “Not only cripples have a need for crutches/And if they/Ever take/You away/From me/I’d fall down… and lie still.”

It was recorded as a total afterthought.

We thought we’d finished work on [second album, 1978’s] A Tonic For The Troops. But by the end of it [producer] Mutt Lange said, “Have you got anything else you can give me?” I said, “Fuck off, we’ve been at this for eight weeks – what do you mean ‘anything else’?” He said, “There’s a central heart to this thing missing.” Well, I’d had these words for ages, just this story which everyone subsequently compared to Springsteen, but my guy was Van Morrison. Because

the mythology of songs like Madame George was far closer to home. Though, having said that, I actually wrote part of the words of Rat Trap while I was back in Dublin, in my flat, reading Woody Guthrie’s Bound For Glory – the same book where the name ‘The Boomtown Rats’ first appears.

For a No 1 single, that’s incredible.

Well, the truth of it is, that song doesn’t exist without Mutt. I had the bare bones of it, which was all around G minor, but it didn’t really move. Then I sang, “Billy doesn’t like living in this town…” He said, “Play it to me again” and put in a D there, and we just kept building it up. It became a hit because we played it on Kenny Everett’s TV show. The next day, you had hordes of punters coming into record shops asking for it. Retailers asking, “When’s that track coming out?” The label comes to us and says, “We’ve got 360,000 pre-orders of a track that isn’t going to be a single.” To get to No 1, though, we had to sell 450,000 and oust John Travolta and Olivia Newton-John, who had been there since forever.

I was in bed with Paula in the morning when the news came through. It was fucking amazing, but I swear to you, the next emotion was fear. I’m not sure the band felt that, but I did – because I was the guy who wrote the fucking songs. I sort of wished I wasn’t, because suddenly you were keeping the band going, the crew going, the office going. That’s a pressure. And you feel it.

Well, you share a language and because of that, you think it’s going to go as smoothly as it did in the UK. But, of course, none of the bands that came through after punk broke America, because [Americans] couldn’t understand the attitude that went with the music. The Clash eventually got through, but that was because of MTV. We go over there and we’re told there are 33 dates of promo and live appearances lined up in the space of 30 days. Cocaine was all over the place. You had Artie Fufkins everywhere chopping out lines and telling you they were gonna bust their asses breaking you in their territory.

But the reality was that you were somewhere in the mid-West working through a schedule that made no sense to you, dealing with a bunch of people who didn’t even know how to pronounce your name. I still have a laminate with the words ‘Brad Gandalf’ written on it.

Well, exactly. The San Diego show was the make-or-break moment. We were co-headlining with The Fabulous Poodles, but it was really our big showcase. Our radio plugger says, “You could break America tonight.” As we’re leaving the hotel to go to the gig, I’m told by our manager Fachtna [O’Kelly] that I’m sharing a cab with this guy in a satin Foreigner jacket and I have to be nice to him because he’s important to my career. Now, I don’t know why, but when someone tells me something like that, it’s like a red rag to a bull. So, fast-forward a couple of hours. From the stage I spot the satin jacket, and I say, “Just a minute.

Can you turn on the lights?” – and I ask the audience, “What do you think of radio in America?” For the first time in your life you’re going to be able to tell the people who program what you hear what you think of them. “See the top of the balcony there? They’re all DJs.” The crowd turned and shouted, “You fucking suck, you assholes! Fuck off!” And they all walked out. Instantly, we’re off the air that night on 60 major stations. When we came off, Fachtna just looked at me and went, “Thanks, Bob.” I felt a cunt, because he was very smart, and he’s my mate. Meanwhile, our plugger’s in tears, because he knows what that means for us.

When you have a hit like Rat Trap, the stakes are suddenly higher, so suddenly everyone had an opinion on how best to follow it up. We re-recorded Joey’s On The Streets Again with Gus Dudgeon and it was fucking horrendous, so it was a matter of seeing what else we had. We’d been in San Diego when the news came through about Brenda Spencer [the schoolgirl who took aim at fellow students and staff entering the school across the road from her bedroom window]. I was doing an interview in Atlanta University. Suddenly, the machine next to me starts spewing out ticker-tape.

This was happening less than a mile away.

So, obviously, you’re absorbing the horror of this event, and then this reporter gets through to the girl and she says, “Something to do. I don’t like Mondays.” If you write songs, the mercenary side of you kicks in. This tragic event is unfolding and among it all, you hear a song title.

Well, the song needed to live up to the title. …Mondays [1979] was originally this sort of reggae thing. It was only when Nigel Grainge heard it and said, “What the fuck was that? It’s a monster!” Johnnie [Fingers] was a big fan of Steve Nieve’s playing with The Attractions, and also Mike Garson with David Bowie – these grand piano melodies, and you can hear that on I Don’t Like Mondays. We went from writing Rat Trap at the eleventh hour for the previous album

to recording ‘Mondays’ for the next one before we’d recorded a note of anything else.

an insurgency which is euphemistically referred to as “the Troubles” and a church which tacitly condones child abuse. It must sting a little bit when The Clash – who were great, but didn’t really change anything – get so much critical adoration. For a while, though, The Boomtown Rats were a bête noire to the Irish establishment. It’s a mark of how antiquated things were that a group like us could still be seen as the Irish Sex Pistols. I mean, it’s 19-fucking-80, and

no venues in Dublin would let us play. So, we’ve hired out the tent and paid host to the Pope’s mass in Ireland the previous year, and we’ve sold 7,500 tickets to play at Leopardstown Racecourse. But by the time we get off the plane from Belfast to Dublin, our insurers have pulled out. Fucking nightmare. Every time we found a venue to erect it, some other residents’ objection would come in. So, we went to RTE and told them we weren’t going anywhere until we had played this fucking show. That was how we ended up playing on the grounds of Leixlip Castle on the outskirts of Dublin after midnight, which was too late for any High Court judge to be alerted to what was happening. Fachtna called RTE and told them the gig would be happening the following evening, without letting on where. The crew worked flat out for 24 hours. Just digging the holes for the toilets took them all night and, by that time, I’m terrified, because I don’t know if word’s going to filter through in time for the show. But by the time I woke up, you had kids travelling from all over Ireland to get to Dublin – just this constant stream of buses depositing people in Leixlip.

Well, in the sense that I could actually do something about it, the timing was good.

Well, as you say, I like a fight. And my big fight towards the end of 1984 was trying to arrest our commercial fortunes. The last time I’d written a hit to order was She’s So Modern [1978], which featured that line ‘She’s so 1970s’ – and, to a lot of people, that’s the decade we should have stayed in.

I didn’t want to do that again, and actually, [1984 album] In The Long Grass had enough great songs for me to not have to do that. But we had this song on the record, Dave [a somewhat prescient song about a friend who had discovered his partner dead next to an empty bag of heroin], which was really our final throw of the dice. I gave Simon [Crowe, drummer] and Garry [Roberts, guitar] £1,000 each and they went around the country to all the chart-registered shops, buying up copies of the record. The rest of us went around the London shops doing the same there. And it might have worked, had it not been for the fact that we were penalised, because some 7”s were on clear vinyl with

a ticket laminated into them, which gave you free entry to any gigs on our next tour. Gallup, who collated the chart at the time, disqualified the single because they said it was a bribe. So that effectively thrust the band into limbo. We didn’t get together once between the recording of Do They Know It’s Christmas? and the Live Aid soundcheck.

Random things pop into your head about that day, often at bizarre times. Recently, it was Prince Charles asking me if I’d managed to “put a few pounds away” – and then Diana, just noticing how very shy she was.

That’s the understatement of the year. The first time she got pregnant, with Fifi, Melody Maker wrote that “someone ought to tell Bob Geldof that one Geldof bastard is enough.” Sounds printed a photo of her with the caption ‘Abortion of the year’. It wasn’t nice.

That’s not entirely true. The record was finished before she died. I wish I’d had a chance to play it to her, actually. At the very beginning, she always wanted to know which songs were about her. And, you know, I think she understood that if you get a good song out of something, then it’s worthwhile. She’d have been flattered I wrote these shitty songs about her.

Someone mentioned the similarity to me shortly after Paula passed away. That really took me aback, but then I went through the words and it’s so on the money. And now when I do it, I just have that in my fucking head.

To see your children lose their mother and to have to guide them through that is hard to imagine. But then, to actually lose one of your children in similar circumstances – well, it’s something you’ve tried to put into words on the new LP, most notably on Passing Through.

It captures that thing of being out thinking you’ve recognised someone you know before you realise that the person you mistook them for is no longer alive:

“I wish that you’d told me/I’m only passing through,” you sing.

Those were just the words that came out. Both with the Rats and on my solo records, Pete Briquette has been my co-writer. It was Pete who coaxed me into singing again after Paula died. And I was at Pete’s when I did the first vocal for Passing Through. You’re in a mate’s house, so you don’t feel like anything ‘formal’ is happening. I just closed my eyes and those were the words that came out. Later, we went into the studio and did other takes, but nothing came close. That’s a thing that no one really warns you about. The older you get, the more frequently one of the dead presents themselves in your head, and you’re suddenly enveloped in a sense of them. And there you are sitting in the fucking traffic and suddenly – boof – you’re in bits.

Well, we’ve all been through our versions of hell. We’re open with each other, and talk each other through it. I mean, we talk now, but we rarely did the first time around. That’s why it’s extraordinary to me that The Beatles wrote letters and postcards to each other when they were apart. Who the fuck does that? Do you think Mick sent a postcard to Keith? Did he fuck!

My guiding stars were New York Dolls, Mott The Hoople and early Roxy. But hey, Suede is a compliment. I fucking love Animal Nitrate and all those things.

I suppose it’s in response to what I don’t hear on the radio. I just wanted… a glorious noise, that’s it.Who’s the female singer on there?

It’s Pete’s daughter, Serafina. But the inspiration was really these girls you see around the S-bend of the Kings Road. That’s where bohemians have made a theatre of themselves since the late-19th century – Oscar [Wilde], I suppose, being the ultimate. But it’s also where Keith and Brian and Mick lived – and they’re all still around there. And it’s also where the Sex Pistols started, and where the rest of us went when we weren’t at Vivienne Westwood’s. Duran Duran went to Antony Price’s shop there, because of Roxy Music. So, it’s an odd little sliver of London. But the main thing now is that there are three quite cool charity shops there, so that’s where I go to look for my groovy shirts.

I was in there on a Saturday, and here was this 15, 16-year-old, chatting to her mate who was working behind the counter. And she looked the fucking bollocks. I loved that. She was this sort of sequined tramp, this sort of living glitterball, and they were moaning about Saturday night, nothing going on, they had no money anyway, and I just thought, ‘So much has changed, and yet nothing has changed. You could write She’s So Modern about these girls now and all you would need to change is the year.’ It seems as though the cyclical nature of life has extended to The Boomtown Rats. Aspiring rock stars leave their

families and form bands, which become their de facto families. Then, when

those musicians start to make their own families, it’s hard to keep a band going.

But eventually, once everyone’s kids have grown up, the musical family can once again reconvene.

It’s funny you should say that, because that’s how it felt the moment we started playing again. With family, you never have to explain yourself. It’s the same with these guys.

It’s dark and the rain is illuminated

by headlights of the rush-hour traffic.

He’sbeen typically open during our time together but, finally, he wants to add something that he’d like to keep “off the record”. What on earth could Bob Geldof have to say that he wants to keep off the record? It turns out that he wants to quote poetry at me – Keats’ Ode On Melancholy,

to be precise. And while your correspondent has always honoured interviewees’ off-the-record requests, an exception surely has to

be made here. “‘Ay, in the very temple of Delight/Veil’d Melancholy has her sovran shrine,’” he recites, before looking straight

at me.

“That’s the key to it, I think,” he says.

“In your lowest moments, you can throw yourself into music and you’re released into this … this rapture. And the one grows out

of the other. All you have to do is keep showing up and stay open to it.