NO END IN SIGHT TO AFRICA'S CHILD HUNGER CRISIS

By Dr Joan Nyanyuki, Executive Director, African Child Policy Forum

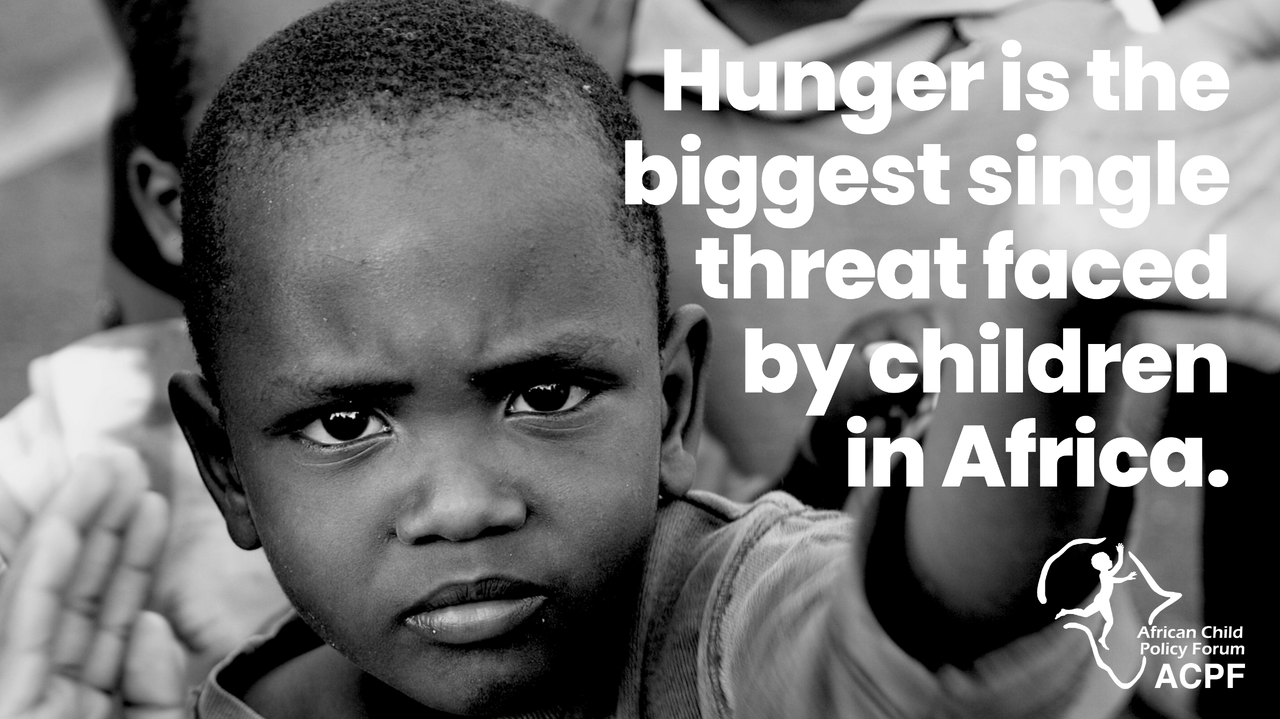

Once again, African children find themselves at the centre of a growing hunger crisis. From the Horn of Africa to the countries of the Sahel, millions of children face a bleak reality of hunger, slow starvation and even death. They are the victims of our inability to learn from past mistakes.

The data makes for grim reading. According to Action Against Hunger, four of the world’s top six “hungriest countries” - Ethiopia, Nigeria, Somalia and South Sudan - are in Africa. Altogether, 19 African nations are listed as “countries with very concerning levels of hunger”.

The headlines are as relentless as they are distressing. According to The Times, 23 million people are on the brink of starvation across the continent. Save the Children reports that more than seven million children will suffer from severe hunger in central Sahel by mid-2023. More than five million people in drought-stricken Kenya - among them nearly a million under-fives - are staring at one of the worst food disasters in the country’s history. Meanwhile, the dire food situation in the Horn of Africa means the hunger crisis there is already worse than the famine of 2011.

Shocking as these figures are, even more shocking are the stories of human suffering which lie behind the statistics. But we should not be surprised. Four years ago, the African Child Policy Forum (ACPF) warned that hunger is the greatest challenge facing Africa’s children; that hunger contributes to nearly half of all deaths in childhood; and that nine out of ten children don’t eat enough nutritious food. We also pointed to the drivers of child hunger: extreme poverty, government inaction, uneven and unequal economic growth, and a broken food system. Add gender inequality, forced displacement, armed conflict and climate change to that toxic cocktail, and we really do have a crisis on our hands.

Trends in tackling hunger make for dismal reading. According to the latest Global Hunger Index (GHI), progress has stagnated in sub-Saharan Africa, while the prevalence of undernutrition in North Africa has actually risen to the highest rate since 2001.

I refuse to accept that child hunger is either inevitable or insoluble. We know the causes are complex, but we also know that child hunger is fundamentally a political problem. Our research shows that African countries which have strong child-friendly policies and allocate sufficient budgets to implement them tend to have fewer hungry children. But even those governments which have taken the problem seriously are now facing wave after wave of challenges: the post-pandemic economic down-turn, increasing severity and frequency of climate-related floods droughts and storms, and armed conflict on a scale not seen for decades.

Conflict remains one of the key drivers of child hunger. Research suggests that around 75 percent of all stunted children under the age of five live in countries affected by armed conflicts, and that the proportion of undernourished children is two to three times higher in protracted conflict zones. 2021 saw 18 sub-Saharan states with active armed conflicts compared to just 12 in 2010. It is no coincidence that the Western Sahel - which saw a fifty percent increase in conflict-related deaths in 2022 - is facing a famine, or that the Horn of Africa, facing prolonged drought and food insecurity for close to 23 million people, is going through several armed conflicts.

Time and time again, ACPF and others have pointed out to governments that there are powerful economic as well as humanitarian arguments for reducing child hunger, and that it is in their own interests to do so. By 2050, Africa will have to feed more than two billion people, one billion of whom will be children. Hunger is a huge drag on social and economic development. It costs African countries an average ten percent of their GDP and threatens the continent’s future growth. Hunger has both short- and long-term negative impacts on children’s physical, psychological and intellectual growth. Children who are hungry or stunted perform worse in school, have low self-esteem and when they grow up, are more likely to be unemployed or find themselves in low-income jobs. This in turn has a significant impact on a nation’s economic success.

There are ambitious projections for Africa’s potential for growth in the coming decades - but that won’t happen if its children are hungry and unhealthy. It is unacceptable on so many levels - morally, culturally, economically and legally - that so many of our children are going hungry. It is also unacceptable that hunger is driven by poverty and inequality, problems that we have created and that we can solve, if we care to. Simple actions can address the wealth and gender inequality that force children from poor and rural areas and girls to suffer the most.

Later this year, ACPF will launch a specially-commissioned documentary on the state of child hunger, No End In Sight. The film’s title prepares you for a heart wrenching story, of the painful hunger that Africa’s children are going through.