Otto Dix's Metropolis: A Painting of Juxtapositions

When analyzing any work of art, we often do so with historical context in mind. Obviously the reason being, that the times in which the artist is living greatly impacts the content of their piece. Otto Dix's Großstadt (Metropolis) is a prime example of this, but what is unique is how inherent in this work of art, contains what in my opinion, are a series of juxtapositions against the time in which Dix is painting; the Weimar Republic.

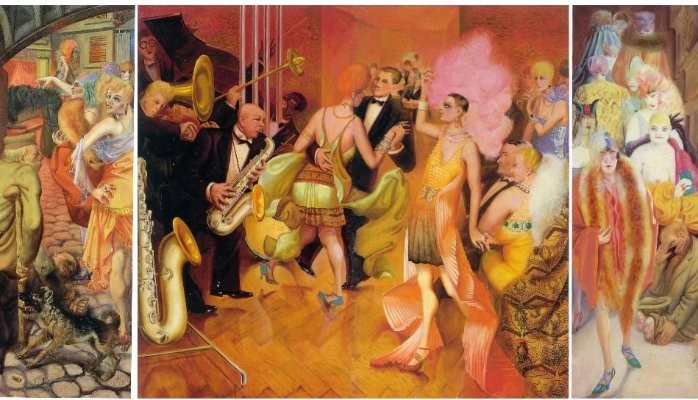

The painting itself dates from the end of the 1920s, a period in German history known as the Weimar Republic. The name itself was simply an unofficial designation of the German state from the end of the First World War, until 1933 when Hitler is made chancellor. What the Weimar Republic is essentially known for is the immense hyperinflation that Germany would suffer, ironically enough while other powers, namely the United States, were experiencing the "roaring twenties". Inflation itself is an economic phenomenon that occurs when too much money is printed, and thus the currency devalues; however, because of Germany's heavy post-war reparation payments, they experienced a level of inflation so high, it was deemed hyperinflation. The crisis is also coupled with the fact that the Weimar Republic was only able to make one payment successfully, thus the situation could not improve for them. It is thus during the period of the Weimar Republic that the famous images of citizens pushing wheelbarrows of Deutschmarks in order to purchase one loaf of bread emerge, and we truly get to understand the economic hardship of Germany. It is this concept of the economic damage of Weimar Republic Germany that we can see a very potent juxtaposition in Dix's painting. The painting itself shows no indication of hardship at all. We are in fact greeted by a scene of elation in which the viewer catches people dancing in what appears to be a jazz club. By the way the people are dressed, by the way we can see them dancing in pure ecstasy, this is a scene that does not indicate an economically-ravaged populace.

Another interesting juxtaposition I observe is in the left panel of the triptych, and this I believe is centered on the veteran. I am under the impression that Dix had placed the veteran in the far panel to symbolize the transition of Germany after the Great War. The presence of the this old, decrepit man, hunched over devilishly clearly contrasts the young and vibrant patrons of the jazz club in the center. The juxtaposition of the veteran is made even more apparent by the fact that Dix has almost satirically depicted him as having lost both of his legs. Dix himself made numerous sketches to showcase the brutality of the Great War (which he himself experienced) that are akin to the nightmarish sketches of De Goya's on the Napoleonic invasion of Spain. It is thus understandable why Dix would try to showcase the brutality of the Great War on his veteran, although in the case of Metropolis it is done obviously as a juxtaposition and satire. He is clearly made not to belong in this scene. What is more up to question however is the look of utter disgust and disdain on his face. This man had lived through the horrors of the Great War and saw death and destruction that no one should have ever witnessed. It would thus be understandable why he would look onto the scene of loose morals before him with such disdain, because it brings into question why would anyone fight for their people only to see such an immense lapse in moral judgement? He had fought for the country that had lost the war and as a result had suffered immensely, yet the people choose to ignore this fact and engage in petty leisure while their country is in ruins. This is also made potent by the fact that I believe Dix has painted him almost to serve as an afterthought. For instance, the only thing acknowledging his presence in the entire left panel is a viscous dog; he is also painted to appear small in a relatively larger image which is noted by his posture, and the fact that we as the viewer view him from behind. His sacrifice for his country is ignored (just as he is in the painting), and it is questionable how he will fit in this new Weimar Republic.

This also brings up another interesting juxtaposition: an overall loosening of morals. The first obvious sign is the simple fact that there is a jazz band. Jazz, a musical form not native to Europe, found popularity as an underground form of expression in cities such as Paris, Berlin, Munich, and Vienna; cities in which underground, avant-garde scenes flourished during the interwar years. Dix has even painted as part of the jazz band a black man, who although is painted in this particular image dripping with negative stereotypes, his place is a testament to the fact that music is in fact a unifying language. Although the United States was going through their "Jazz Age", in many countries grounded in tradition, such as Germany with their tradition in the Romantic symphonies, Jazz was vilified for its intense syncopation, its wild melodies, and the raunchy dances that were accused of corrupting youth. It is thus understandable why Dix would choose a jazz club if his intention were to show a juxtaposition. Indicative of the Jazz Age is obviously the way people dress in this painting, and Dix makes it a point to not miss a detail. Short and low-cut dresses, bright colours, feather boas, exposed shoulders, we can say with confidence for its time this scene would have been considered to be highly immodest, dripping with innuendo. Lastly it is apparent in the left panel of the triptych we are greeted by ladies of the night. Dix makes this clear in the way that he positions the blonde woman, how she has her hands on her hip, her leg very much exposed, and has a look of smug confidence. Not to mention the fact that there is an inebriated man at the mouth of the alley. All in all the loosening of morals apparent in this painting is an obvious juxtaposition by Dix to the highly mundane and deprived days of the Weimar Republic. As such, Dix would later find himself as a part of the Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition of the Third Reich in 1937 which was meant to showcase art that was deemed "un-German" in nature and content. The scene we witness in Metropolis is thus soon to be merely a nostalgic memory of the past.

I would like to finish off on some thoughts towards the far right panel because visually this one is a juxtaposition to the other two. It uses a much lighter, softer, colour palette which gives it a more dream-like luster. What is also notable in this one compared to the other two are the rather expressionless faces of the people. These people are clearly dressed the same as the other patrons of the painting but yet they engage in no revelry, and they stare blankly towards the viewer. Perhaps this was Dix's way of saying that the good times we see expressed overall in Metropolis, are about to come to an abrupt end, and the expressionless faces represent the uncertainty towards what will greet Germany in the years to come. There is an obvious sign of uneasiness, but at this point they are blind and unsure towards what awaits them and the world, with the advent of Nazism and the rise of Hitler.

Private Mortgage Specialist at Savers Mortgage Inc.

7yExcellent written thesis!!!!