History of Science & Technology, Including Fossils, Minerals, & Meteorites

History of Science & Technology, Including Fossils, Minerals, & Meteorites

The 1969 Nobel Prize Medal in Physics Awarded to Murray Gell-Mann, for his work on the theory of Elementary Particles

Lot Closed

April 28, 08:03 PM GMT

Estimate

200,000 - 300,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Gell-Mann, Murray

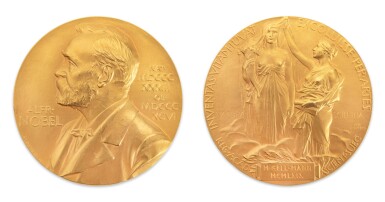

THE 1969 NOBEL PRIZE MEDAL IN PHYSICS, AWARDED TO MURRAY GELL-MANN, ONE OF THE LEADING PARTICLE PHYSICISTS OF THE 20TH CENTURY, FOR HIS GROUNDBREAKING WORK ON THE THEORY OF ELEMENTARY PARTICLES

Nobel Prize medal, struck in 23 carat gold, designed by Erik Lundberg and manufactured by the Swedish Royal Mint. Obverse with bust of Alfred Nobel left, in field left, ALFR·/ NOBEL; behind head to right, NAT·/MDCCC/ XXXIII/ OB·/ MDCCC/ XCVI; at left edge, before bust, E· LINDBERG 1902. Reverse with, INVENTAS · VITAM · IUVAT · EXCOLUISSE · PER · ARTES (Life is enhanced through the arts of discovery) — REG · ACAD · — SCIENT · SUEC · (The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences); below, incuse, on tablet in exergue, M · GELL-MANN / MCMLXIX, Nature, in the form of a goddess, standing left, her right arm holding a cornucopia, a figure representing the Genius of Science, standing right, holding up the veil of Science; in field, left, NATURA, in field, right SCIENTIA / ERIK / LINDBERG; the edge marked MJV (Mynt ochs Justeringsverket [Royal Mint and Assay]) GULD 1969; weight: 182.57 g.; diameter: 66 mm (2 5/8 in.). Housed in the original red morocco case, top of case with border of a double-gilt rule and gilt dot-fillet, corner tools, and recipient's name (M. GELL-MANN) in the center; the fitted interior lined with suede and satin; interior case edges with gilt dentelles.

AND: Murray Gell-Mann's 1969 Nobel Festival Personal Program, in original oblong black leatherette case (6 x 3 1/2 in) (Front cover of printed program with “Gell-Mann” misspelled “Gell-Man”, and corrected by hand in blue ink).

THE 1969 NOBEL PRIZE IN PHYSICS AWARDED TO MURRAY GELL-MANN, ONE OF THE LEADING PARTICLE PHYSICISTS OF THE 20TH CENTURY, FOR HIS GROUNDBREAKING WORK ON THE THEORY OF ELEMENTARY PARTICLES, RECOGNIZING THEIR HIDDEN PATTERNS AND FINDING A WAY TO ARRANGE AND CLASSIFY THEM ACCORDING TO THEIR PROPERTIES

Born in 1929 in Lower Manhattan to Eastern European immigrants, Gell-Mann was a child-prodigy. He graduated valedictorian of his high school at the age of 14, received his Bachelor's degree at Yale at the age of 18, before completing his doctoral dissertation at MIT just two years later in 1951. He became a member of the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, doing his post-doc there under Robert Oppenheimer, before heading to the University of Chicago to work with Enrico Fermi. It was there that he would develop theories of strangeness (a quantum property which accounted for decay patterns of certain mesons) and eightfold way (an organizational scheme for hadrons, which led to the development of the quark model, named, much to his regret later on, after the Buddha’s eight-step path to enlightenment).

In 1955 he moved out West to teach at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), becoming their youngest full professor just a year later. It was here that he met Richard Feynman, a fellow professor of theoretical physics, and the two would go on to become friends and sometimes rivals. The pair would do important work together, and in 1958 (in parallel with Sudarshan and Marshak) developed V-A theory, discovering the chiral structures of the weak interaction of physics. The pair were quite the contrast to each other, Feynman with his irreverent personality, eschewing ties and coats and speaking in a thick Brooklyn accent, in contrast with Gell-Mann, who was always careful to correctly enunciate every word (in multiple languages!) and was known for being impeccably dressed. Though they chose to go their own ways rather than continue to collaborate in physics, they remained close colleagues; their offices were next door to each other, and Helen Jane Tuck was their shared secretary.

In 1964, Gell-Mann, along with George Zweig postulated the existence of quarks. Zweig referred to them as “aces”, while Gell-Mann co-opted “quarks” from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (“Three quarks for Muster Mark!”). Gell-Mann’s name is the one which stuck, and soon after, gluons, quarks, and antiquarks were established to be the elementary objects in the study of the structure of hadrons. Shortly thereafter, in 1968, the existence of quarks was confirmed by researchers at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, and a year later, Gell-Mann became the sole recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physics, for his “contributions and discoveries concerning the classification of the elementary particles and their interactions”. As the headline of his obituary in The New York Times stated, he truly “Peered at particles and saw the Universe.” (May 24, 2019). This achievement deeply impressed Gell-Mann’s friend & colleague Richard Feynman. Feynman routinely refused to recommend colleagues for the Nobel Prize, but he broke his rule in 1977—after Gell-Mann had already won the prize once—and quietly nominated Gell-Mann and Zweig for their invention of quarks. (Gleick, Genius, p. 396)

In 1984 Gell-Mann co-founded the non-profit Santa Fe Institute, the world’s leading research center for complex systems of science. Gell-Mann served as director of the Macarthur Foundation from 1979-2002, was on the President's Committee of Advisors on Science and Technology from 1994-2001, and fittingly for a man who was nicknamed “The Walking Encyclopedia” as a child, he was a member of the board of directors of Encyclopedia Brittanica Inc. He was a member of the National Academy of Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, as well as a Foreign Member of the Royal Society. In addition to the Nobel Prize, his numerous awards and honors include amongst others: the Dannie Heineman Prize for Mathematical Physics (1959), the Ernesto Orlando Lawrence Award (1966), the Franklin Medal (1967), the National Academy of Sciences John J. Carty Award (1968), the Albert Einstein Medal (2005), and the Helmholtz Medal of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities (2014).