Greater expectations

Reality TV they are not, but two hit shows are so convincing as imitations of life in the criminal justice system that some legal experts worry they’re distorting the expectations of real jurors.

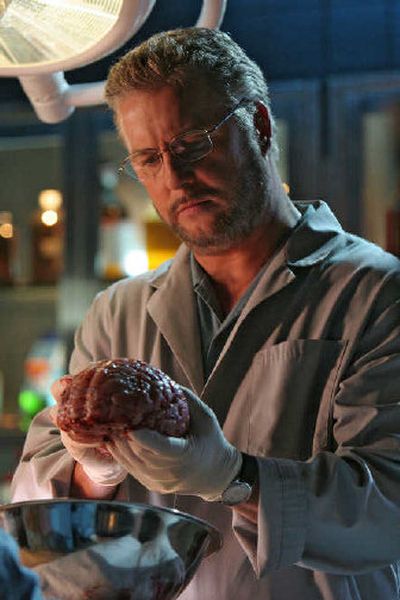

The influence of the “CSI: Crime Scene Investigation” and “Law & Order” franchises has permeated American law. Lawyers ask would-be jurors whether they watch the shows and then change strategies depending on the answers. Law schools maintain video libraries of the programs as teaching tools and even analyze the plot lines in class.

Which side benefits the most – prosecutors or defense attorneys – is debatable.

While “Law & Order” glamorizes prosecutors, “CSI” can set standards for the infallibility of forensic evidence that prosecutors can’t often meet – a science-solves-all formula that millions of viewers may bring to jury service.

There is no debating, however, one clear, very widespread result of these programs: The justice system is now facing what legal experts call “the CSI effect,” a TV-bred demand by jurors for high-tech, indisputable forensic evidence before they will convict.

“These programs have a potential for great mischief but also for great learning,” said Laurie Levenson, a Loyola University (Los Angeles) Law School professor who discusses “Law & Order” in her classes and whose school maintains a library of episodes.

“CSI” dominates network rankings for CBS with versions set in Las Vegas, Miami and New York, while “Law & Order” and its spinoffs are an NBC stalwart. A single first-run episode of “CSI” can draw 26 million viewers while a “Law & Order” episode averages 11.4 million.

Multiply that by spinoffs and cable reruns, throw in other crime-based series, and there’s a virtual world of crime-show junkies who could end up deciding guilt or innocence in real trials.

“The expectations of jurors are more elevated,” said Elissa Mayo, assistant lab director for the California Attorney General’s Bureau of Forensic Services. “They think that we have all the space-age equipment that they see on TV and before you come back from the commercial break you have the results.”

In response, scholarly law journals have included articles suggesting that prosecutors warn jurors at the outset that it can be very difficult to obtain forensic evidence and that circumstantial evidence is sufficient to prove a case.

The problem is that many cases have little forensic evidence, notes Michael Asimow, a UCLA law professor who teaches a course on law and popular culture.

“Shows like ‘CSI’ are teaching people that without forensic evidence you can’t convict anybody,” said Asimow.

In Baltimore, for example, less than 10 percent of homicide cases in the state attorney’s office in 2004 involved fingerprint or DNA evidence. Evidence, instead, often was circumstantial or reliant on eyewitnesses.

In one case, an 11-year-old girl pointed at a defendant and said, “That’s the man who shot my father.” But jurors found him not guilty.

One later explained: “I would have liked to see some evidence, like finding the gun with fingerprints.”

In last year’s murder case against Robert Blake, prospective jurors were asked whether they could fairly evaluate evidence that prosecutors contended would show the former tough-guy actor killed his wife.

“Oh, that’s easy,” said one prospect. “I’ll just go by the DNA.”

A prosecutor informed the potential juror there might not be DNA evidence, and as the case played out, there was none. Forensic testimony focused on a smattering of gunshot residue and blood spatter and the claim that police mishandled evidence – an issue stressed in Blake’s successful defense by attorney M. Gerald Schwartzbach.

Schwartzbach acknowledged that jurors probably were more receptive to his hours of laborious cross-examination on scientific details because of their exposure to TV forensics shows – though he dismisses those shows as “electronic relatives of tabloid journalism.”

The fact that a forensic expert with a gun could possibly contaminate evidence doesn’t bother Ann Donahue, executive producer and co-creator of “CSI Miami.”

“What we’re doing is entertaining,” she said. “It’s like a medical show. When you go to the hospital, you’re not going to find that doctor you see on TV.”

Dick Wolf, who launched the “Law & Order” franchise 16 years ago, traces his show’s roots to a pitch he made to the late NBC chief Brandon Tartikoff for a program based on “the front page of the New York Post.”

“And that’s still it,” he says. ” ‘Headless body found in topless bar’ is still a great story.”

The “Law & Order” series frequently offers thinly disguised dramatizations of high-profile cases. But Wolf says the shows are more than mere entertainment.

“I think we have raised people’s awareness of how the justice system operates, how evidence is obtained, the conflicts between cops and prosecutors, why evidence is excluded that the jury never gets to see,” he said.

Defense attorney Thomas Mesereau Jr., who won acquittal for Michael Jackson on child molestation charges in a case with almost no forensic evidence, said he rarely watches “CSI” or “Law & Order,” but doesn’t object to jurors being educated by TV.

“I think we’re better off if the public understands what techniques are available,” Mesereau said. “I have great faith in American juries and I would like to think that they know a lot of these shows are pure fantasy.”

But sometimes that fantasy does alter the reality of a case.

Last year in Texas, the conviction of Andrea Yates in the drowning deaths of her five children was reversed because of an error involving “Law & Order.”

Forensic psychiatrist Dr. Park Dietz, a key prosecution witness and one-time consultant for the show, testified that an episode in which a woman drowned her children in a bathtub aired before the Yates killings.

Prosecutors suggested Yates concluded from that episode that she could get away with the murders. However, it turned out there was no such episode and Dietz has admitted he was mistaken.

In reversing Yates’ conviction, an appeals court said his testimony could have affected the judgment of the jury.