Two genres, kabuki actor prints (yakusha-e) and the beauty prints (bijinga) of Yoshiwara, dominated ukiyo-e visual culture throughout the Edo Period in Japan. Landscape prints (fūkeiga) remained a minor genre until the 1720s as they did not conform to the pursuits of the pleasure quarter. However, the changing social and political context of the Edo Period stimulated the creation of a new avenue of subject matter within ukiyo-e print culture. Fūkeiga consisted of an array of outdoor endeavors including pilgrimages, sightseeing, festivals, and day-to-day activities.

A number of factors brought about the landscape paintings of two exemplary artists: Hokusai (1760-1849) and Hiroshige (1797-1858) . Censorship of kabuki actor prints and beauty prints set the stage for a new avenue of prints. Increased interest in travel coupled with the introduction of Prussian blue color truly spurred on the landscape genre with full force. Without these developments, it can be argued that the popularity of landscape prints would not have reached such preeminent levels.

The Era of Hokusai and Hiroshige: Government Censorship of Ukiyo-e

The strict government regime of the Edo Period passed a number of controversial edicts that restricted artistic freedom in the production of popular ukiyo-e prints. For example, they prohibited the illustration of actors, courtesans, and geishas. It is important to note, however, that artists and publishers often developed ingenious ways to continue to create popular subject matter while complying with censorship laws. With subtle changes, such as the use of anthropomorphism to depict courtesans or actors, artists could accommodate these regulations.

The continuity of prohibited subject matter demonstrates the inefficacy of censorship enforcement. Those responsible for policing the laws were in fact members of the publishing and printing industries. Therefore, by subtly disguising prohibited but popular themes, potential financial gain would not be threatened. The development of “veiled dissent,” novel but decipherable devices used to comply with censorship rules, created a new aspect of excitement to visual culture and became a popular feature of ukiyo-e prints. For this reason, it can be argued that censorship was not the most significant force behind the rise of the landscape genre. It was more due to the increased interest in depicting nature and tourist attractions, coupled with new artistic technologies and inspiration.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

Inspiration from Chinese Painting Manuals

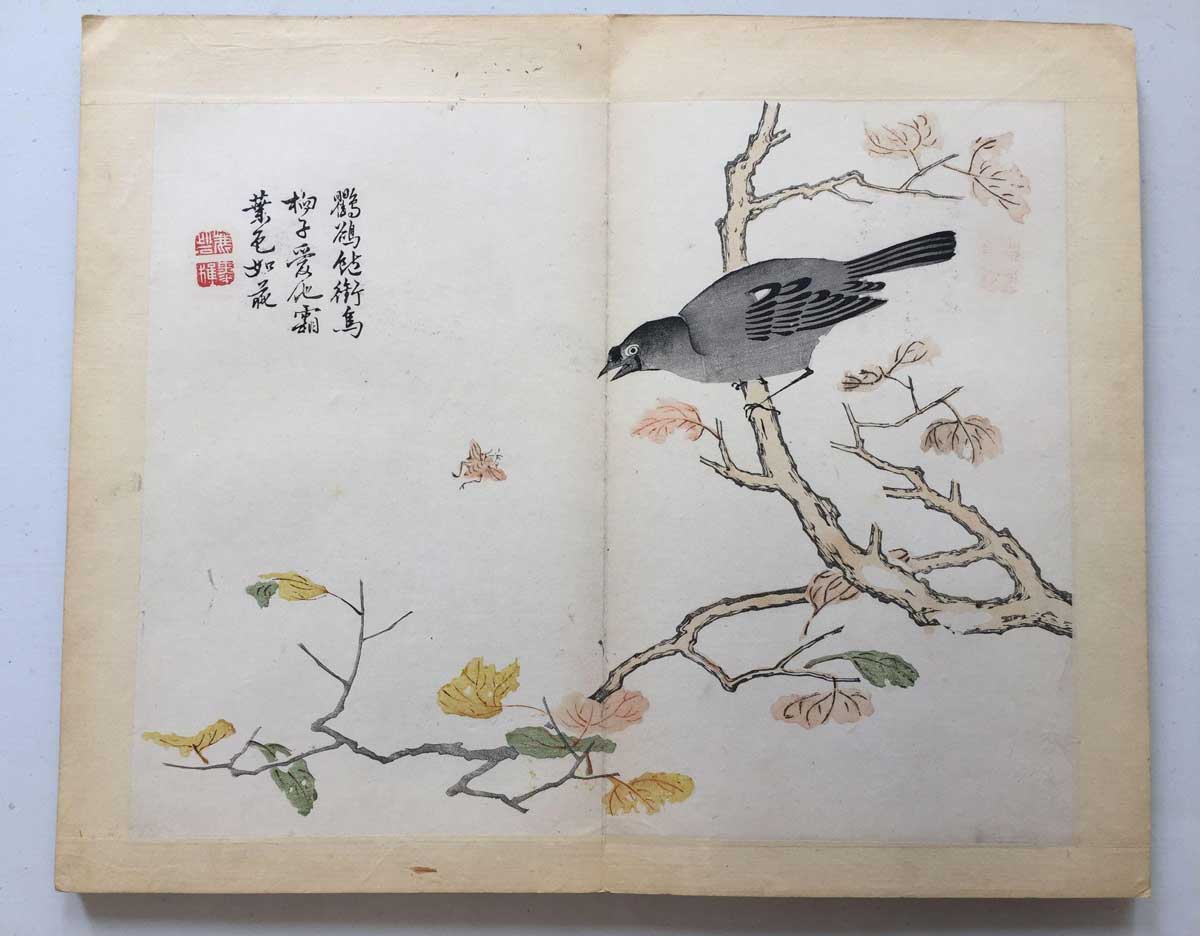

Existing painting manuals, particularly from China, aided artists in depicting this new genre. Since 1639, Japan had isolated itself from the rest of the world, however, trade with the Chinese and Dutch at the port of Nagasaki was maintained under strict measures. It was here that Chinese manuals and paintings entered Japan as guides to basic theory and techniques. They were broadly emulated and they greatly impacted the training of artists as well as the development of landscape painting in the Edo Period.

The Eight Different Picture Album originally published in China between 1621-28, then, reprinted in Japan in 1672 and 1710, served as the first great pictorial source on Chinese painting for Japanese artists. It contained themes of orchids, birds, and chrysanthemums as well as techniques in using brushes, ink, and colors. Another preeminent Chinese source is the color-printed manual, The Mustard Seed Garden published by Wang Gai in 1679 which included different landscape forms such as rocks, trees, and mountains, in a variety of styles.

Furthermore, painted folding screens of scenes in and around Kyoto served as a point of reference for visualizing certain scenes of Japan’s native landscape, not that of China. These sources were predecessors of ukiyo-e landscape prints. Hokusai and Hiroshige would have used such manuals and other similar publications as a template to depict the views of distant places they had not visited themselves.

A Desire to Travel Japan

During the Edo Period, public interest in visiting places beyond one’s own residence increased considerably, facilitating the growth of landscape prints which provided townspeople with an insight into these scenic areas without even having to leave the city. Nishiyama Matsunosuke, a cultural historian, has described this emergence of expanded travel and increased curiosity as a “culture of movement” or kōdō bunka.

Initially, travel was limited to members of the military or court nobility for purposes of official business, notably the alternate attendance system (sankin kotai), or pilgrimage (mairi). During the Nara and Heian Periods, the word tabi (travel) had negative connotations signifying venturing into the unknown. But from the late to mid-Edo Period, as a result of peace and prosperity, travel as recreation and pleasure became possible for the common people of Japan.

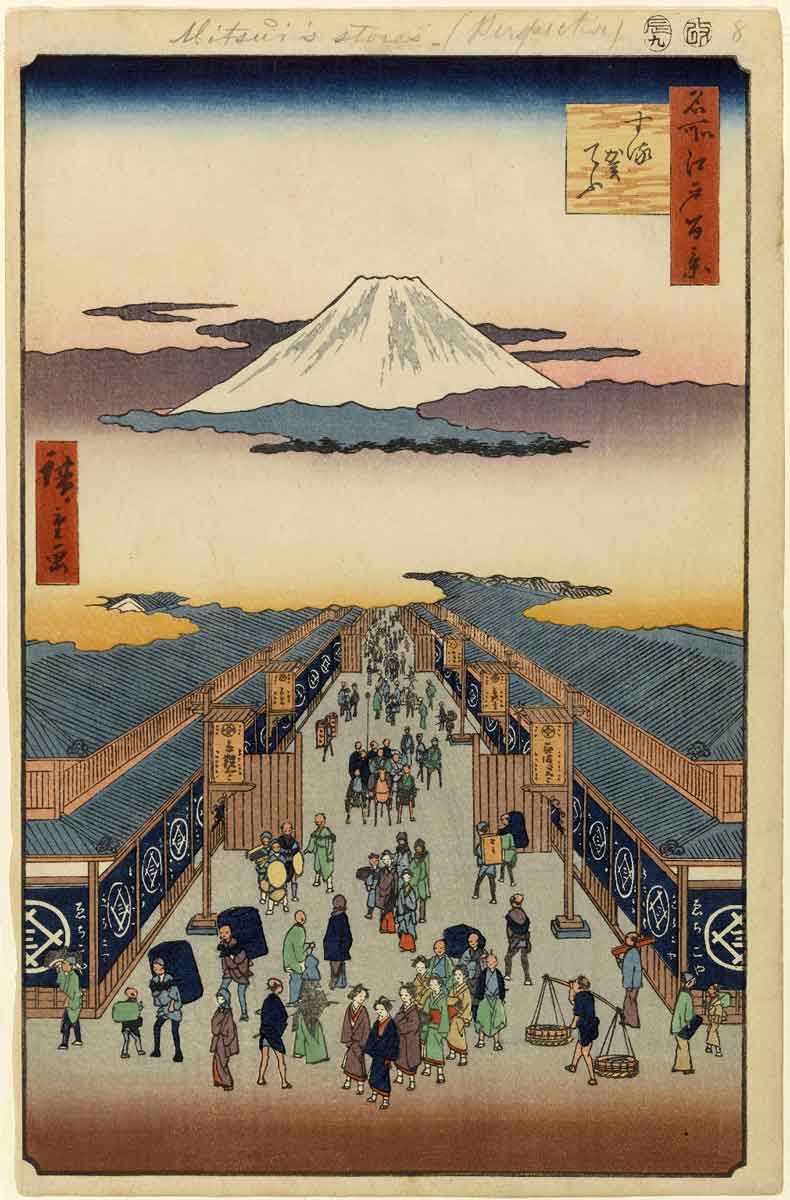

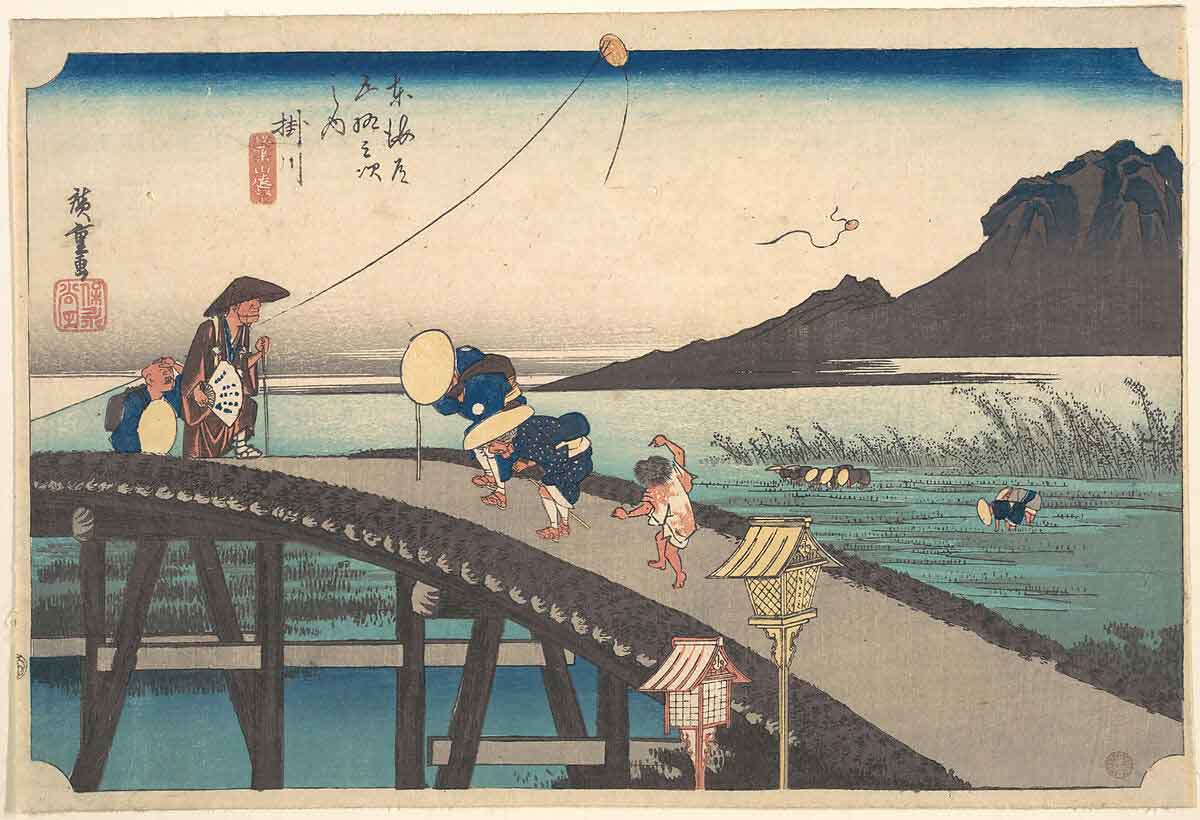

Fūkeiga allowed sightseeing and leisure pursuits from the perspective of townspeople to be echoed in Edo prints. Some bought prints as keepsakes/souvenirs from actual journeys or as collectibles within a series, while others purchased them to appreciate places that they had never traveled to but wanted to experience. They also served as a form of escapism; creating an enticing and reassuring landscape compared to the harsh realities of Edo which was consumed by economic distress and political conflict. Essentially, travel kickstarted a popular sub-theme of landscape prints which intensified the demand for such representations.

The “culture of movement” was prominently expressed in and promoted by meisho-e (“famous sites prints”). It was to see meisho that people wanted to travel. The affordable medium was a major innovation in the 1830s and contributed greatly to the success of landscape prints as an independent genre. Scenes from Edo included picnickers observing the spring cherry blossom in Gotenyama and Asukayama, summer firework displays over Ryōgoku, autumn leaves covering the grounds of Kaian-ji temple or Nihonbashi glistening in the New Year’s snow. The increasing popularity of discovering one’s own country and famous places rooted in Japanese society and culture influenced Hiroshige and Hokusai to create such images for ordinary people to possess and collect.

The Tōkaidō highway was of particular importance in the depictions of meisho. This 550-kilometre coastal road facilitated access by directly linking the capital of Edo with the imperial court of Kyoto. Initially, travel was limited to the daimyo and their entourage under the sankin kotai; feudal lords were required to alternatively reside between the imperial court and the capital. However, as travel became more accessible, merchants on business as well as ordinary people sightseeing or on pilgrimage undertook the three-week journey. These images, serving as visual souvenirs, provided insights into post stations, lively hubs of lodgings (hatagoya) and tearooms, as well as the scenic routes from the highway.

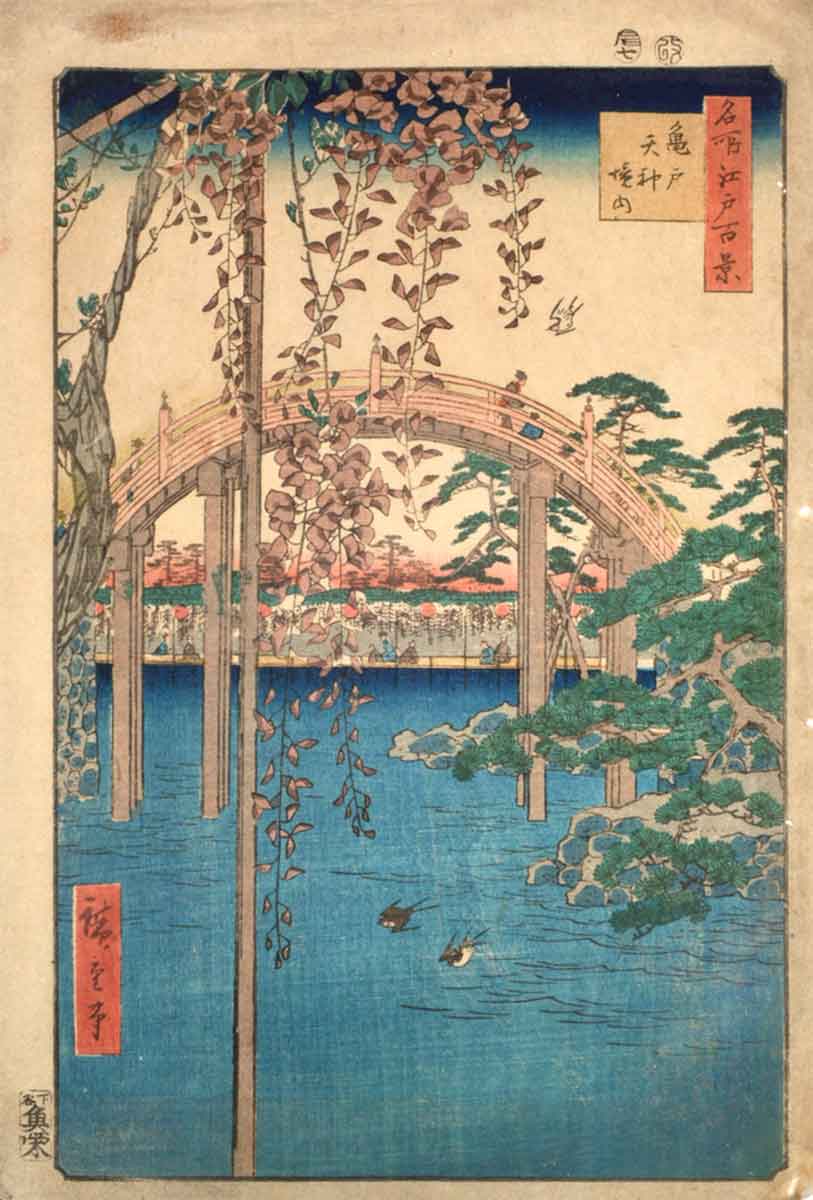

Finally, landscape paintings were enhanced by the innovative creation of Prussian blue. The first modern, artificially manufactured color, bero, more commonly referred to as Prussian blue, was first synthesized, accidentally, by Johann Jacob Diesbach in 1706. Importation into Japan derived either directly from Dutch traders or more likely via China where it was manufactured from the 1820s. By 1829, it had become widely used in Japanese prints.

Prior to the discovery of Prussian blue, few blue pigments existed for printing, most of which had certain limitations. Azurite (iwa-gunjō) and smalt (hana-gunjō) generated rich tones, yet their large particle size prevented the smooth surfaces necessary for woodblock printing. Furthermore, aigami, extracted dayflower petals (tsuyukusa), yields a perfect blue, however, over time areas of pale brown appear due to its light sensitivity. Natural indigo (tade-ai) was also widely used yet has a low tinting strength, therefore, large amounts of this expensive pigment were needed in order to achieve the desired color.

In comparison, Prussian blue is finely separated allowing a smoother, more even finish that is less prone to fading. In addition, its high tinting strength allows a little to go a long way, ensuring its commercial viability. It is no wonder then that this ideal bright blue pigment dominated Japanese prints throughout the Tenpō Era thus becoming a driving force for landscape success.

It is often argued that Hokusai’s Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (1830-1832), which included the famous The Great Wave, served as a crucial catalyst for the “blue revolution” and thus landscape painting. This series, published by Moriya Jihei, consisted of ten designs in chuban form, depicting the power and beauty of Mount Fuji, Japan’s sacred mountain, from different locations.

It was the first major series in which Prussian blue was applied, propelling Hokusai to new levels of popularity. The series was originally intended to be produced in a single color, aizuri-e, encouraged by publishers who profited from the trend. Aizuri-e were created with only blue ink but tonal variations were achieved by using the bokashi technique (color gradation). Bokashi was easy to implement and earned considerable success in landscapes as great blue expanses such as sky and water could be rendered vividly. Even though only a single color is used, the image still depicts both the beauty and severity of nature. Standing precariously on a rock outcrop, a fisherman casts into the violent Fuji River. Hokusai fuses man and nature into one as the body mimics the waves below.

Despite blue remaining an integral element in the design of every print in Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, Hokusai included a number of color combinations. Take for example, the distinctive bright green of Hokusai’s landscapes, a mixture of Prussian blue with sekiō, (orpiment yellow) which enhances the serenity of the landscape. Or, the safflower red (beni) developed by printing multiple layers to create deeper hues, as epitomized by Red Fuji.

The emphasis on strong coloring, the red mass displayed against the blue sky filled with intricate cloud patterns, heightens the dramatic presence of the mountain within the scenery. Hokusai’s series ignited other artists to depict the beautiful conical form such as Hiroshige, in his One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji. It is clear that the introduction of Prussian blue ignited an experimentation with the use of color, depending on the ways it reacted with other pigments. Its expressive qualities coupled with Prussian blue’s vibrancy and durability created dramatic designs thus enhancing the appeal of landscape prints for a popular audience.

The Emergence of Hokusai and Hiroshige

The emergence of the two great landscape artists, Hokusai and Hiroshige, was caused by a fusion of social and political factors. Censorship edicts, such as the Kansei and Tenpō reforms, set the stage for a new genre, however, if it were not for the driving forces of artistic technologies and new inspirations, then fūkeiga would not have filled this void. For example, the accessibility of Chinese painting manuals laid the groundwork for landscape techniques, forms and compositions.

Furthermore, the emergence of travel for the common people of Edo provided inspiration for the subject matter of landscape artists. The popularity of these visual souvenirs maintained its market and propelled the genre to heightened success. Furthermore, without the introduction of Prussian blue, these depictions could not have been completed to such a high standard. All of these coinciding factors led toward an era of artistic innovation and fortunately for the artistic heritage of Japan, skilled individuals like Hokusai and Hiroshige were able to capitalize on this moment.