Much taller and more bulbous than I am, Jeff Koons’s Balloon Venus reflects the viewer on every bulge and curve of its magenta-coloured, mirror-polished stainless-steel body. The reflections are meant to make us feel somehow included, though all those twists and eruptions remind me of strangulated hernias or a monstrous yet cutesy haemorrhoid.

Making a balloon sculpture from the late paleolithic stone statuette known as the Venus of Willendorf – an object that could sit comfortably in your hand – then using a CT scanner to fabricate this vastly enlarged version strikes me as excessive. The original tender stone-age figure, rediscovered in Lower Austria in 1908, sits in a museum in Vienna, while Koons’s Balloon Venus is exhibited in the middle room of his show at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

Balloon Venus stands among larger-than-life polychromed stainless-steel ballerinas – all based on east European porcelain figurines – whose makers might, just might, have once glimpsed a reproduction of a Degas dancer. Their execution is a marvel. I would call them breathtaking but for the queasiness of their belated rococo frivolity. The eye slithers over their shiny surfaces. I can imagine Hermann Göring loving them.

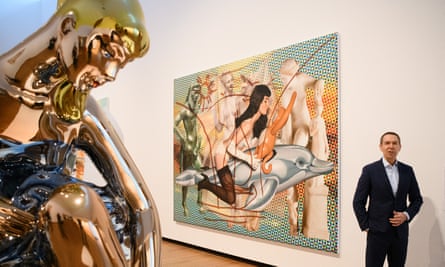

Various classical floozies look out from a number of paintings. Their photographically derived forms are overdrawn with blownup graffiti riffing on Courbet’s 1866 L’Origine du monde – which is to say, scribbled vulvas. One large image depicts actor Gretchen Mol riding an inflatable dolphin, while ogling a blowup monkey toy. Koons says he realised at some point that the monkey was Eros, and that Mol, in her acting role as 1950s pinup model Bettie Page, was the goddess Aphrodite. Ah! Antiquity!

Dizzy with the air-headedness of it all, I can’t even get into Koons’s sexual politics in this room of female fancies – never mind the skills and the quality of craftsmanship involved in every stage of their misconceived execution.

I like the basketball in the aquarium best. It greets you as you walk in. Hovering in midwater, this is the earliest work in the show. Koons’s One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank from 1985 is a reminder of the promise he once had, before he embraced Banality. Then came the inflated silver bunny, the carved kids and the happy pig, the blue gazing ball in a pristine birdbath. The first room in the exhibition takes us from 1985 to 2013 in four easy steps, providing a precis of his ascension into decline.

But maybe his art was always iffy, as we critics have it. According to the catalogue entry to the basketball piece, Koons had the help of “Nobel prize-winning quantum physicist Richard P Feynman” in devising a method for keeping the ball hovering at the right depth (the trick involves distilled water and salt). Whether he needed the brainpower of Feynman to get the job done is questionable, but anything that adds extra oomph and glamour, or a flashy backstory, is fine by Koons. As the late singer-songwriter Reg Presley recommended in the notorious Troggs Tapes, a sprinkling of bastard angel dust over the fucker always helps.

In the last room, Koons’s version of Titian’s painting Diana and Actaeon is a remarkably accurate transcription of the 16th-century original, right down to the pattern of cracks in the surface, although I haven’t counted the number of arrows in Actaeon’s quiver, or the leaves on the trees. It is but a few centimetres smaller than the original. What really gives the game away, apart from the lack of Titian’s impasto brushwork, is the large blue blown-glass ball resting on a little shelf affixed to the lower part of the canvas.

A further transcription, of Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (1818-19), is a great deal smaller that the French artist’s original, and appears to have been copied from a digital image that shows the original painting prior to its most recent cleaning. No matter. All this is interesting, but only insofar as Koons, or rather his army of assistants, should have devoted so much time, skill, technology and, most of all, money to the devoted reproduction of these and other paintings and sculptures. “Every brushstroke is applied by hand,” the wall text tells us, and “each glass ball is hand blown, and for each one that is sufficiently flawless to be used in an artwork, around 350 end up being rejected.”

The works in the last room of the exhibition, with their references to Titian and Rubens, to French Romanticism and classical sculpture – the Belvedere Torso, Praxiteles’s Silenus with baby Dionysus, appended with these perfect blue balls, fulfil an art historian’s fantasy of the continuity of tradition – and a secret desire for the end of art.

One cannot compare the stupendous lengths Géricault went to in creating the Raft of the Medusa (storing body parts, including severed human heads, in the studio as models for his emaciated figures) with Koons’s mostly fiscal labours, in keeping his show on the road. Koons’s art is too expensive to fail, I have heard it said. It will survive as a paradigm of folly and excessiveness, less to be looked at, more to be gawped at.

Jeff Koons is at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, from 7 February until 9 June.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion