Have we stumbled into an era of sexual ennui? Particularly as we age and couple up, do we increasingly drag our weary, uninspired carcasses to bed, and … nothing? Nada. That’s that.

Robbie Williams has been talking about his sex life with Ayda Field, his wife of 13 years. “Everyone knows there is no sex after marriage,” he said, musing that stopping taking testosterone was probably partly responsible for his drop in libido. Williams continued: “Sometimes now, Ayda will turn to me on the sofa and say, ‘We should do sex’, and I’m sitting there eating a tangerine and just sort of shrug.”

Turning down sex? Tangerines? Shrugging? Let’s be clear, the couple are wildly happy together. But bear in mind this is Robbie Williams, Cosmopolitan’s Most Sexiest Man in the World 1999, with the shredded musculature, the tattoos, the actual job description of “sexy pop star”, and, at 49, in the prime of silver fox-dom. If Williams is declaring there’s no sex after marriage, should we consider it on a par with a landmark scientific discovery? Or is it more a sign of the times, and we’re all unsexy now?

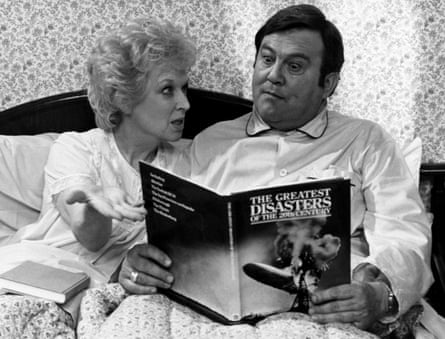

Think of sexlessness within marriage, or any long-term relationship, and certain unwelcome images spring to mind, mainly from ancient British sitcoms: Terry and June in matching brushed-cotton sleepwear. George fighting off a lascivious Mildred. For those too young to get these references, the basic tenor is sexual death in suburbia – erotic entombment beneath candlewick bedspreads. Something few ever want, or believe will happen to them.

Yet, here we are, with a pop god munching a tangerine and breaking what could be the last genuine taboo: talking about sexlessness within marriage. Maybe it’s time to lift this particular rock and see all that’s dark and wriggling (and not wriggling) beneath. To ask, what is (and isn’t) going on sexually in British marriages, and why don’t people want to talk about it?

First, it’s time to bust the age-old myth that the British hate talking about sex. Sometimes, looking around, it’s as if sex is all we talk about. However, often long-term couples only want to talk about a specific kind of sex – the sort that “other people” are having (vague wave of the hand) “out there”. Such musings go beyond heterosexuality, bisexuality, pansexuality, and the like (it’s so passe to be concerned about all that), into the realms of BDSM, polyamory, dating apps, “orbiting”, “breadcrumbing”, hook-up culture, and so on.

Basically, whatever youngish or single-ish people are doing, long-term committed couples are talking about them doing it. Sometimes with relief that they’ve managed to give it all a swerve; other times, with a kind of wistfulness – like it’s a “freaky sex” windfall they’ve missed. What the married are far less likely to debate is their own amatory reality. The little clockwork figures hastily retreat back into the cuckoo clock of long-term coupledom. Cue the shame. The stigma. The anxiety. The envy (thinking that everyone else is always at it). And the outright fibbing – let’s call it “sex-washing” (pretending you’re always at it).

It’s all guesswork (does anyone truly know about the lives of others?), but you’re left with the impression of a bizarre hidden phenomenon – the masked incel – those who are in committed long-term relationships, even married, but for one reason or another are not having sex. Those for whom familiarity hasn’t bred contempt but has triggered baked-in sexual abstinence.

In 2019, the British Medical Journal, surveying data from around 34,000 Britons, found that one-third of men and women had not had sex in the past month. Moreover, the biggest fall (since the research was previously conducted in 2001) was among the over-25s and couples who were married and living together. In 2020, another survey, conducted among around 12,000 Britons and published in the BMC Public Health medical journal, reported that most people grouped into the “low interest” sexual category were married or living together.

Then factor in the steadily falling birth rate (though, of course, sex doesn’t have to mean procreation). And the voluntarily celibate (vol-cels?): at the beginning of the year, Google Trends data showed a 90% increase in searches for “celibacy” in the UK. While a recurring theme in having less sex/no sex is ageing, are we generally as a nation less interested in sex? Not according to a recent survey which rated Britain the fourth “horniest” country in Europe, coming in pouting and smoothing our eyebrows after Italy, Spain and France. Though seriously, who’s to judge anyway? Clearly, for those in happy celibate couples, sex is not the glue, nor is it synonymous with true intimacy.

There are also long-term committed couples who are having lots of sex, and they’re great at it. After all, arguably, there’s a better chance of a more varied and imaginative sex life within a long-term relationship – as opposed to hook-up culture, which, at its most mechanical, might lapse into repeating the same moves with different partners. In certain cases, maybe it’s the committed couples who are the true “hotties” walking among us. That’s the plan anyway, so why isn’t this blissed-up nirvana happening as much as it should?

Short answer: life. In otherwise healthy relationships, the Great Turning Off/De-Sexing seems caused by an avalanche of potential stressors. Work pressures. Health difficulties. Parenting stress. Looking after your own parents, financial problems, housing, the cost of living crisis. Then there’s the increase in lifespans (thus having to sustain relationships longer). The weight of expectation in post-dating app culture. Even the fact that some people are drinking less alcohol and must learn the dark art of sober sex.

It could be about impotence, other sexual problems or lack of body confidence. Or the proliferation in recent decades of hardcore pornography (reported to lead to erectile dysfunction, even in young males). It could even relate to the female orgasm gap: a 2019 Ann Summers survey of 2,000 people conducted as part of its Pleasure Positivity Project revealed that women were missing 1,734 orgasms in their lifetime.

Put like that, it’s a miracle anyone manages to get it on. Certainly, it explains how, with the best will in the world, the drained and the desperate temporarily go off each other. How some couples may even resort to following well-meaning advice to drag each other out on stilted “date nights”, to “communicate openly and honestly”, “share puddings sexily”, and all the other things that would make any sane person want to claw out their own entrails and then lie sobbing in them.

Of course, I’m being facetious (well, apart from “share puddings sexily”). More seriously, is there really that much to worry about when, at some points in a relationship, even in this era of uber-erotic plenty, an otherwise solid couple encounters a good old-fashioned retro sex-drought? Is it, historically speaking, even borderline normal to slide into friendship-mode for extended periods? It’s just that, these days, people (looking, feeling and acting younger in so many other ways) expect their lives to be considerably sexier. As in: “I confidently use emojis and I still go to music festivals, therefore I should be having a lot more sex.”

In reality, are Robbie and Ayda so wrong, so out of step? Aren’t long-term relationships designed to sexually wax and wane? Sometimes a couple are all over each other, sometimes they’d rather eat citrus fruit. Whatever works for them is fine, and to torment themselves about what others are doing is as pointless as it is torturous. To finish with a quote from poet and author Charles Bukowski: “Money is like sex. It seems much more important when you don’t have any.”