New perk! Get after it with local recommendations just for you. Discover nearby events, routes out your door, and hidden gems when you sign up for the Local Running Drop.

It’s the first day of competition at the Tokyo Olympic Games and in Fukushima the Japanese women have downed the Australians 8-1 in softball, a victory symbolic of the region’s recovery from the disasters eleven years ago. It’s still two days until the opening ceremonies and five until triathlon action gets underway, but the Olympic Village is starting to fill up, jets paint Tokyo’s noontime blue skies with interlocking white rings, and road closures snarl traffic for locals across the city. Rainy season has broken just in time for the sun and a drier heat to welcome the Games, and down at the triathlon venue the heavy rains have left the water quality of Tokyo Bay a beer bottle transparent brown that smells of nothing but the sea.

Hidden in the shadows of the pandemic and overlooked for a while now, another problem has suddenly risen to the surface again: that brownish water. Now added to the bay are a number of one-of-a-kind systems, including a three-layer barrier to block bacteria from entering the swim area and generators to then stir up and cool down the water if it gets too hot.

RELATED: On the Ground at the Games That Almost Didn’t Happen

The question of water quality at the swim venue first came up at the 2019 test events. Two weeks before the triathlon test race, athletes competing in marathon swimming, held at the same location as the triathlon swim in Tokyo Bay’s Odaiba area, complained that the water smelled “like a toilet.”

Shortly after, water quality tests before the paratriathlon test race recorded E. coli levels twice the allowable level set by World Triathlon. The swim was canceled and the event was carried out as a duathlon. “It was bad,” said Ben Collins of the water at the time. Collins is a former pro on the ITU circuit and now a guide for a para athlete Aaron Scheidies. The swim familiarization for the mixed relay was also canceled, but test results the next day returned values within the limit and the actual relay race went off as scheduled.

Odaiba, the area hosting the Olympic triathlon, is a waterfront district in the innermost region of Tokyo Bay. Its dates back to the Edo period in the mid-1800s, when the area was built up from reclaimed land in order to play home to a battery of cannons that were intended to prevent American Commodore Matthew Perry’s Black Ships from landing and to stop the U.S.’s attempts to force Japan to open to the West. Odaiba’s beach park was built in 1996, and the area is now a hub of shopping malls, luxury hotels, and high-rent high-rise apartment buildings. People fish, play beach volleyball, and enjoy water sports like standup paddleboarding and windsurfing, but things like swimming and diving that involve going directly in the water are strictly forbidden.

The reason is the water quality. Normally, the water quality here is simply not deemed good enough for the general public to swim in.

With exemptions for the special event, Odaiba has however been the site for the Japan Triathlon Championships every October since 2001. Air and water temperatures at that time of the year, though, are typically around 65 degrees F, a radically different situation from what athletes will face at the Olympic race this weekend. Sports that require wind and waves, like surfing and sailing, took their events to neighboring prefectures Chiba and Kanagawa, but short of traveling out to Tokyo’s distant southern islands there’s really no other choice for waterfront venues within the city. This is it.

Tokyo Water Quality: Science to the Rescue

All of which gave Tokyo another hurdle to clear as host city. “Even since before 2019 we’ve been working on solutions for this issue of water quality,” said Koichi Yajima of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s Bureau of Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games Preparation. The solution? A “high-tech” system that keeps out bacteria—and then deals with the compounding heat challenges.

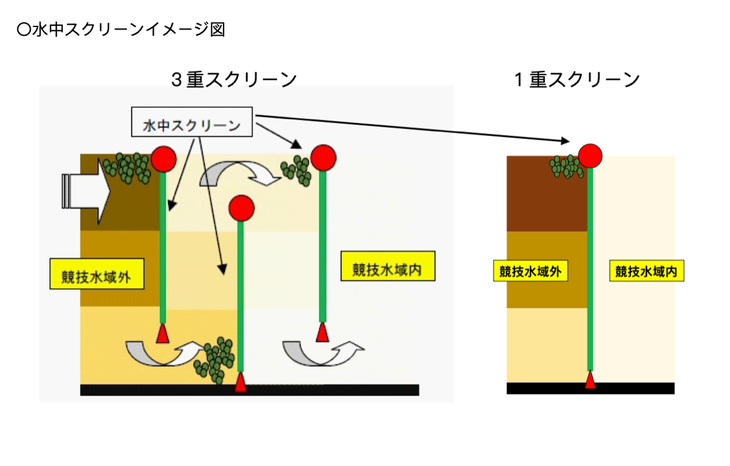

“One method that has been recognized as effective has been the installation of barrier screens to prevent the inflow of impurities. For the Olympics we have upgraded that to a triple layer of screens, which has proven highly effective,” said Yajima. While there was just one layer blocking bacteria from entering the swim area back in 2019, there are now three layers. Experiments on the efficacy of the screens found that even in circumstances where E. coli levels exceed the allowable limit when using a single screen, the triple screen method will reduce the levels by as much as 80%.

At the same time, though, those three layers also stop water from flowing in and out of the swim area—which causes it to heat up. It has been demonstrated that water temperature can rise about 1-2.7 degrees Celsius (about 2-6.5 degrees F). Official guidelines call for the swim distance to be cut in half if the water temperature hits 30 degrees C (86 F) and to be canceled at 32 degrees C (89.6 F). With temperatures at the test event just squeezing under at 29 degrees C, water temperature has become a key variable thrown into the mix. The city’s quick-fix solution was another novel one: large generators to circulate the water if it gets too hot.

Again, science comes to the rescue. “Water flow generators have been installed to gently circulate the warmer surfer layer and replace it with cooler water from the depths,” Yajima said. “In this way we can keep water temperatures from rising.”

Another measure was the depositing of two tons of sand from the remote island of Kozushima in February 2020. Covering the more polluted seabed of Tokyo Bay with clean sand encourages the growth of native marine organisms that naturally purify the water. The city has also expanded collection facilities to control the flow of rainwater into the bay during periods of heavy rain, which should also impact Tokyo Bay’s water quality. Although sewage and rainwater are not separated in much of Tokyo’s historic sewage system, they are treated separately in the Odaiba area and sewage does not flow directly into the bay. But in times of heavy rainfall, runoff may still enter the rainwater flow from further upstream. The new facilities aim to prevent this. “There was talk that the water in Odaiba smelled like a toilet, but with regard to sewage treatment Odaiba employs a split-flow system,” Yajima said.

RELATED: Why Triathletes Should Be Fierce Advocates for Clean Water

Has It Worked?

Tokyo may have been undertaking these infrastructure advances in time for the Olympics, but how much has the water quality actually improved? According to Hayato Okada of the Tokyo Olympic Games Organizing Committee’s PR bureau, water quality tests conducted daily at the Odaiba venue since July 1 have indicated no problems with the water when the weather was good. At the same time, testing indicated that there was still a decline in quality one or two days after heavy rain. Less than a week before the start of triathlon competition these results have yet to be made public.

World Triathlon mirrored Okada’s words, with a spokesperson saying, “TOCOG is conducting a daily test for the last two weeks, with samples taken each day in five different locations of the body of water—four of them inside the barriers, one of them outside—and all the results are within the limits. All results will be made public and available for athletes and coaches to check at the Athletes’ Lounge.” But as of this writing, this has yet to happen.

No matter what measures organizers take, nothing can stop heavy rains from falling or hot midsummer temperatures from skyrocketing. What will happen if water temperatures or water quality readings go over the limits? According to Okada, “the use of alternate days and shortening of distance” are issues to be discussed between the Organizing Committee and World Triathlon. This means that beyond just the options of shortening or canceling the swim, there is a possibility that the date of the Olympic triathlon could be changed.

No matter how far the readings fall within acceptable levels or how often organizers say conditions are “safe,” there’s no escaping the fact that all the rivers in the megalopolis of Tokyo flow into the bay, and that it’s just not realistic to expect the water there to be absolutely clean. This is a fate common to all urban triathlons. When you listen to what the athletes have to say, it’s easy to see that the issue of water quality in the triathlon isn’t unique to this year’s Tokyo Olympics but a commonality across events held in metropolitan environments. Water conditions at the London Olympics fell short of receiving full marks and were subject to the same effects of heavy rain as in Tokyo. Water quality was a major concern before the Rio Olympics, and it has been reported that nearly two-thirds of the athletes who competed at the 2009 ITU Seoul event got sick after the race.

The lack of clear data from the organizers at this late stage may be part of what has kept it in the minds of athletes at Tokyo 2020. One voiced skepticism, saying, “The way that World Triathlon or the LOC tests the water will always produce a result that says it is ‘safe to swim in,’ but that doesn’t necessarily mean that there isn’t some amount of sewage, run-off or whatever that can take a heavy toll on a body.”

But most also said they weren’t overly concerned and the risk was in line with many other urban events. To minimize the risk of GI distress in advance of the big day, many athletes said they will likely skip the swim familiarization. Even if access to an indoor pool is strictly limited due to the COVID-19 countermeasures, they just don’t want to take the chance before race day.

USA Triathlon is comfortable with the technical steps that have been taken to ensure water quality and temperature, with a spokesperson saying, “We are confident that all involved organizations are taking appropriate measures to ensure the health of all those competing at the Olympic and Paralympic Games in Tokyo is protected.”

And Yajima echoes the sentiment, voicing calm. “When you get down to it, there’s no chance water quality readings will go over the limit without very heavy rains,” he said. “Water quality in the bay is dependent on how much water flows in due to rain far upstream. Our triple screen measures are there to control for this.” Five days out, the forecast for the first day of triathlon competition on July 26 calls for cloudy skies and a chance of rain. The world’s best triathletes will have to hope that rain doesn’t come down too heavy too soon.

Obsessed with the Olympics? So are we. Get your fix with our round-the-clock coverage of triathlon racing in Tokyo.